ROTTWEIL, Germany — They called her Baqiya, Arabic for “she who remains.” She moved in the highest echelons of the Islamic State, serving Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi tea, pricking her ears as the former “caliph” and his top commanders planned attacks, playing with his children and accompanying his main wife, “Um Khaled,” to ladies’ dos. She was enslaved by Baghdadi’s most trusted lieutenant, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani. The Syrian from Idlib was the Islamic State’s chief strategist and official spokesman, a brute in the bedroom as in the battlefield. He relished killing and bred Arab horses. Then, unexpectedly, he fell in love.

Her real name is Sipan, after a mountain in her native Sinjar in northern Iraq. We met her on a recent morning in a small town in southwest Germany, home of the eponymous guard dog the Rottweiler and a swelling population of refugees. Her smile was serene, her eyes at once gentle and sad. “Welcome,” she said, leading a woman reporter and an Arabic-language translator to the first floor of a modest house near the local cemetery. A jumble of shoes were piled outside the door of the apartment she shares with three brothers, two sisters and a pet bunny.

Sipan Ajo emerged six months ago from seven years of captivity in Syria. She is from Kocho, the mud-caked village in the Yazidi-dominated Sinjar region to which the jihadis laid siege in August 2014, rounding up hundreds of men, pumping bullets into them and dumping them in large holes. Women deemed beyond childbearing age filled them, too, in a gruesome exercise repeated across Sinjar. The younger women and girls were herded off to Mosul and Syria to be marketed as sexual slaves or “sabayas.”

Myriad accounts of their plight have seeped out since, with Nadia Murad, the Nobel Prize laureate who is also from Kocho, among the first females to speak out on the horrors endured by the dwindling religious minority that was brutally persecuted for centuries and vilified as devil worshippers.

The orgy of rape and bloodletting is thought to have claimed at least 10,000 Yazidi lives and is officially recognized as a genocide by the United Nations and numerous other international bodies. The hunt for their remains is ongoing as the Iraqi government continues to exhume dozens of mass graves across Sinjar. This week, another exhumation of seven mass graves took place in the village of Hardan.

In a November interview in Erbil, the capital of the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Hazim Tahseen Bek, the “mir” or prince of the Yazidis, said 3,550 Yazidis had been rescued so far but that a further 1293 women and 1470 men remain missing. “We continue to rely on smugglers' networks to bring our girls back home, but with each passing year our hopes fade,” Bek said.

Sipan, however, rose from the dead. Her family had dug a symbolic grave for her alongside that of her father and her eldest brother, both killed in the Kocho massacre, believing Sipan had died in a 2017 coalition airstrike on a building in Raqqa, the erstwhile capital of the Islamic State. She almost did, one of several brushes with death.

“Sipan was held by the very top leaders of the Islamic State. She showed enormous courage and managed to survive. Her story is unlike any I’ve heard, yet it’s certainly true,” Bek said. “You must tell it.” I promised I would.

Three months later, Sipan sat with quiet dignity on the living room couch, her hands folded neatly on her lap, and described her ordeal in detail to a journalist for the first time. There is no trace of self-pity. She refuses to be a victim. “I want to be the voice of all the girls and women who shared my fate, an ambassador,” she said.

Sipan Ajo with her brothers Nechirvan (L) and Majdal (R), in Rottweil, Germany, Feb. 18, 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

The initial days mirror the gruesome accounts of fellow survivors — being herded into a school in Kocho and stripped of all their valuables, watching helplessly as the men were taken away in dirt-smeared pickup trucks, then being separated from her mother and siblings and moved with other younger women and girls to a holding pen in Raqqa. Her fate, however, took an unusual turn when Adnani, the second-in-command to the late IS leader Baghdadi, made his entrance, flanked by his Algerian guards.

Adnani, then 38 years old, was bearded, paunchy and of medium height. He wore a dark tunic and matching pants and his head was swathed in a black-a-white checkered keffiyeh. He removed his sunglasses and inspected the girls who were forced to stand in rows. He spotted Sipan immediately as she cowered on the floor. He pulled her up by her hair when she refused to rise and pushed her to a corner.

He picked three other girls, a pair of sisters from Sinjar city and another from the Syrian town of al Qahtaniyah and drove them to his villa in the Al Doubad neighborhood on a street locally known as “Robbers Avenue.” Sipan, then 15, was the youngest.

“It was a big villa with two stories, a swimming pool and a garden. He took us to the second floor and locked us in a room. The windows were sealed and shuttered. We were in a state of shock. We couldn’t eat. We were terrified, wondering what had happened to our families. We said nothing. We just cried all the time,” Sipan recalled. “But he didn’t touch us.”

On the third day they were driven to the town of al-Bab close to the Turkish border where Adnani’s wife lived with her two children, mother and brother.

“She was tall and white, and around 20 years old and her name was Betul. She told us to call her ‘my lady’ and to ‘put your head down and say yes when I ask you to do anything.’ She made us do all the housework and fed us leftovers. They were very rich. She treated us like slaves. When Adnani came she would lock us up in a room. She wanted to keep us out of his sight. Her mother was treating us better. When she saw us cry she would come and embrace us and say, ‘I know this is wrong. You can call me aunty.’”

The purpose of the sojourn was to convert the girls to Islam. Betul’s brother, Abu Mujahid, was a well-known sheikh in the area. He taught them to read and recite the Quran and about the life of the Prophet Mohammed. “I don’t believe in any religion after what happened to me,” Sipan said.

A month later, assured of their conversion, Adnani took them back to the villa in Raqqa. It was late at night. They huddled in their room fearing the worst. He came upstairs and shouted, “Why are you sleeping in the room?” Sahira, the oldest at 24, responded, “This is better for us. This is what we want.” Two hours later he returned, dragging Sahira away and locking the door on the rest. “After half an hour we heard her cries. We were shaking in terror until we fell asleep,” Sipan said. “He came back at five in the morning and said, ‘Come down, let’s pray.’ When we went down Sahira was in a horrible situation. He had raped her. There was a mattress on the floor and because of what we saw on it we knew what had happened. I started screaming. He came out of the shower and led the morning prayers.”

The next night he came for Khaleda, the girl from al-Qahtaniya. The following night he raped Sahira’s sister, Jihan. Thereafter, Adnani appeared around midnight every night, in his tactical vest and suicide belt, to take a girl. “They came back like corpses. They never said anything.” He never asked for Sipan. “I was beginning to hope he would not touch me.”

A month had gone by when one morning Adnani sent the girls off to be shared among his guards, but not Sipan. Her heart froze. She thought of throwing herself out of the window, but the house was surrounded by his men. “He came that night and took me downstairs. I kicked him and scratched his face, trying to keep him away. He tied my wrists to the feet of the couch, and started hitting me as he covered my mouth with his elbow. I fainted. I didn’t realize anything until the sun rose. I started screaming. He kept me tied to the couch and raped me again and again before and after prayers.” The nightmarish routine continued for months in the room upstairs. “He made me take pills so I would not have a baby,” Sipan said.

Taha Subhi Falaha, aka Abu Muhammed al-Adnani, was chief of foreign operations for the Islamic State. (Islamic State media)

It didn’t take long for Sipan to realize Adnani, a native of Syria’s Idlib province, was a powerful man she could “use as a weapon for my escape.” Top IS operatives frequenting the villa called him “the catapult of the Islamic State." "He was educated and seemed to know a lot of things. He wrote books, including ‘The Golden Chain in the Workings of the Heart.’ These books were recited on Islamic State radio,” she said.

As the head of IS’ external operations who referred to US President Barack Obama as “the mule of the Jews,” Adnani oversaw a broad network of operatives who carried out terror attacks in Paris, Brussels and Dhaka, Bangladesh. The United States placed a $5 million bounty on the Syrian’s head.

In a September 2014 voice recording posted by IS’ Furqan media group, he is heard saying, “Put forth your efforts to kill any American or French or any of their allies. If you can’t use an IED or gun, then isolate him and smash him with a stone, or slaughter him with a knife, or throw him off a cliff or run him over with a car. If you’re unable to do that, then burn his house or car, or his shop or his farm. If you’re unable to do that then spit in his face. And if you don’t, then take a good look at your religion.”

Sipan feigned submission to win his trust. A couple of months into her enslavement, she was allowed to move around freely within the house. She began cooking and cleaning for Adnani, including his office where he would write on his laptop and sign various papers. He taught her how to cook Mandi rice, a Yemeni meal prepared with meat and spices.

The guards were no longer permitted to enter the house.

Could she make any phone calls? No, Adnani did not carry a mobile phone.

Adnani began conversing with her. “He gave me perfumes, nightwear and fake jewelry. He forbade me to wear long dresses and or to tie back my hair. He said he would cut off my hand if I disobeyed.”

“He began to respect me, too. To say ‘please’ when asking for something.” Her plan was working. Adnani was falling in love.

He told her about his personal life, how he studied Islam before he moving to Iraq in 2000 to join “the jihad.” His real name was Taha. “He always said to me, ‘You are a source of comfort when I talk to you.’ He didn't know that I was planning revenge.”

Soon Sipan was allowed to enter his office to serve tea and sweets to his guests. Al-Baghdadi and a woman who Sipan described as his “most important wife” called Um Khaled, or mother of Khaled, would visit the villa every few weeks. Baghdadi wore civilian clothes under a gold-trimmed black cloak. “He wanted to look like a religious man.” He sported a turban and carried a stick.

Various IS bigwigs, including the Chechen commander Abu Omar al-Shishani, also attended these meetings where new attacks were planned.

Adnani began taking Sipan with him on excursions. He liked having her at his side at all times. They would go to different military camps, including those run by women. “He wanted me to be strong like them. He believed I could become a good Islamic State leader.” He taught her how to use a gun and took her to the banks of the Euphrates River for target practice. Occasionally they would go to a farm outside the city where he kept his Arab steeds.

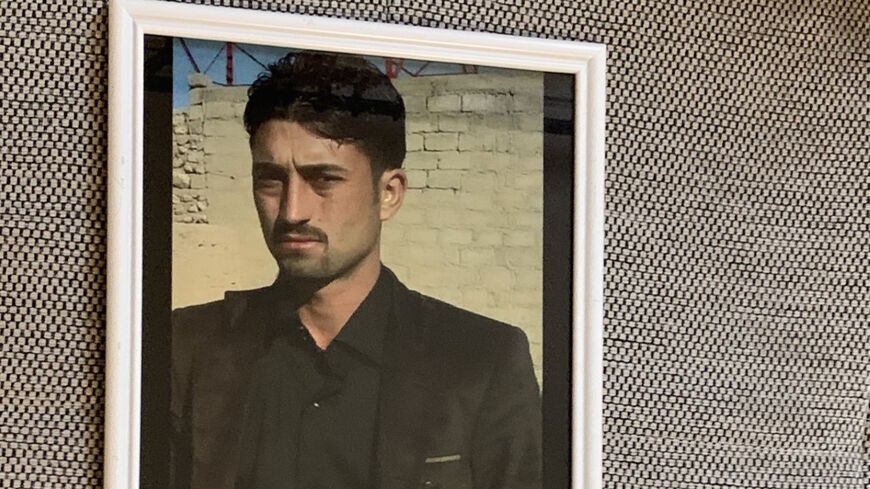

A photo of Ibrahim Ajo, 19, who was killed by the Islamic State on Aug. 15, 2014. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Outside, Sipan would have to fully cover herself with a black cloak, a head covering and a face covering— the abaya, hijab and niqab. Squinting through its slits, she began to accumulate what she hoped would prove to be valuable information. She needed to record it all. She stole a notebook and a ballpoint pen from his office, then asked Adnani for a teddy bear, saying, “I miss my toys.” He duly obliged.

She began filling the notebook with descriptions of the people she saw, what they said and of the secret locations Adnani took her to. What of her own feelings? “I wrote those down too,” Sipan said.

She used the bear to conceal the notebook. She slit its back, removed some of the stuffing to make room and sewed it back up. “I was hoping to get it out for the world to read,” Sipan said. “Even if I died.” Buffeted between her determination to remember and a powerful urge to forget, her sense of time grew fuzzy and she has difficulty recalling precise dates.

The freakishness of Sipan’s new life apparently knew no bounds. Adnani took her to watch Royal Jordanian Air Force pilot Muath al-Kaseasbeh, who fell captive to the jihadis in late 2014, being burned alive. She was the only woman present for the spectacle. “I had seen decapitated heads, corpses, but that day I entered a new world,” she said.

A 20-minute video of his execution in the desert near Raqqa was posted by the jihadis on Feb. 3, provoking a global outcry. It shows a militant in combat fatigues, his face obscured by a mask, holding a torch to the kerosene-drenched line leading to the cage where the 22-year old pilot is being held. Sipan says that man was Adnani. It was as if he was trying to impress her. “I want the pilot’s family to know this. They deserve the truth,” she said.

Adnani trafficked Yazidi girls, some as young as nine. They would be brought to the villa in batches and held there for two days at most. He did not touch them. A man called Abu Omar al-Urduni would buy them from Adnani and take them away for sale in Turkey, Lebanon and the Gulf countries. Sipan was forbidden to speak to the girls and made to shower them and dress them in new clothes. Adnani would ask her if she knew of any of them. She didn't. It broke her heart, but she had to stick with her plan.

As her revulsion grew, so did Adnani’s obsession with her. He acquiesced to her demands to see her family. “I had no idea what had happened to them.” Adnani arranged to have Majdal, one of her younger brothers who then 11 was being forcibly trained as a “cub of the caliphate,” and their mother and youngest brother Nechirvan, then five, to stay with Sipan for a week. She learned that her mother and Nechirvan were being held in a separate detention center in Tal Afar in Iraq “as bargaining chips” for prisoner exchanges. The wife of her slain brother, who was pregnant at the time, had been enslaved with her two children. Her whereabouts were unknown.

“My mother could not bear it. She had a heart attack after she saw Sipan. They took her to hospital,” Majdal recalled. That was the last time Sipan would ever see her in the flesh.

Adnani’s infatuation did not go unnoticed by the Baghdadis. “He began treating me almost like a wife. He asked them to be respectful to me and they were.” His “main” wife Um Khaled took her to women’s gatherings in Raqqa, where tips on how to torture disobedient sabayas were exchanged. Sipan was not accepted as their equal but nor was she treated like a sabaya. Her status was unique.

Adnani began taking Sipan to Baghdadi’s villa in Mosul. “We went there at least four times.” She wasn’t required to wear the niqab in his presence.

Paintings by Sipan's sister Peyman, in Rottweil, Germany, Feb. 18, 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Drawn by her natural magnetism, it didn’t take long for Baghdadi to engage with her.

“I asked him why you killed our brothers and fathers, and why you raped the girls and separated mothers from their children. He started explaining to me about the past centuries and how Muslims used to kill infidels and capture women."

"I asked him, ‘Are we infidels?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I responded, ‘How are we infidels while we worship god?’ He told me that all religions are false except Islam."

“We talked for hours and he thought that he convinced me. At the end, he told me, ‘You are a strong and bold girl who will benefit us a lot,’ and then he said to me, ‘From now on your name will be Baqiya.’"

It was a sick play on the Islamic State motto “Baqiya wa tatamaddad,” Arabic for “remaining and expanding.” Not for long.

By 2015, the “Caliphate” was beginning to shrink as the US-led coalition rained bombs and its Syrian Kurdish allies battled the jihadis on the ground. In August 2016, Western news outlets reported that Adnani had been killed with his bodyguard in a coalition airstrike near al-Bab. It was described as a major coup. Sipan’s world collapsed anew.

The Baghdadis took her back to the villa in Mosul. “Adnani had entrusted me with them so they felt responsible for me.” Life was not that unpleasant. Freed of Adnani, Sipan would spend long hours with his son Khaled and daughter Wafaa, playing soccer in the garden as she once did in Kocho with other kids from the village. “I love Cristiano Ronaldo,” she said of the Manchester United forward, her face lighting up for the first time. Wafaa and she were the same age, Khaled a year older. She confided in Sipan about how her father would rape the Yazidi girls who were brought to their house while her mother looked on. “Wafaa was nice,” Sipan recalled.

Still, that she was “living with people who killed other people” never left her mind.

The house was “like a fortress” and Baghdadi had a library full of books. One of his younger brothers whose real name she doesn’t recall — “only his face” — lived with the family. He was tall, thin, had darker skin than Baghdadi and gray in his beard. The children called him "Ammu," Arabic for uncle. He took off for Turkey one day with Baghdadi’s three-month old daughter Nusayba. She had a hole in her heart and she was going to be treated there. They didn’t come back.

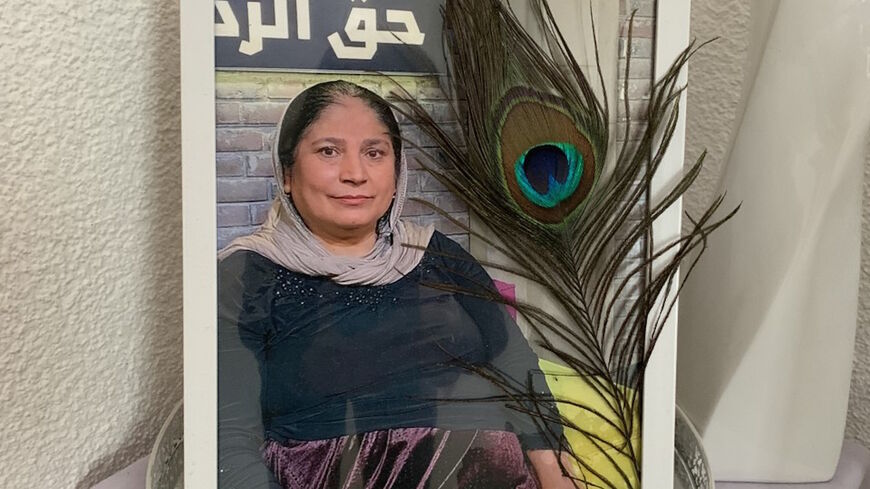

A photo of Sipan's late mother, Majida, in Rottweil, Germany, Feb. 18. 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Three weeks later the family disappeared, leaving her behind locked up in the basement. Coalition strikes were intensifying and Baghdadi had to move. Sipan could tell her status was changing and fast. They returned a day later. Her situation then took a sharp turn for the worse. Um Khaled walked in on her as she was writing in the diary. “What is that?” she asked. Um Khaled ripped it out of her hands and began reading. Her face darkened.

Sipan was thrust into the basement where Baghdadi began beating her, prodding her flesh with an electronic shock baton as he grilled her about who she had shared her secrets with. The torture went on for weeks. “I was expecting something worse than death.”

Baghdadi tried to rape her as tall and hefty Um Khaled helped to pin her down. But their work was interrupted by a wave of coalition airstrikes. Sipan was off the hook.

So why had they not killed her? Perhaps it was out of deference to Adnani’s memory. She was his “wassiya,” his property, and had been willed to them. But then why would Baghdadi try to violate her? Whatever the reasons, Sipan was sick and weak and coalition forces were closing in. In October 2016 they decided to get rid of her and sent her to the family of a low-level IS militant in Raqqa.

He was married with two children and lived in a small apartment. Sipan had developed anemia and chronic gynecological problems due to coercive sex. His wife would take her to the hospital for treatment. Those were the only times Sipan was allowed outside. “The wife was kind to me.” Sipan was confused and depressed. She doesn’t remember their names. What was the point? She had lost everything. “The notebook was my winning card,” she said. In January the militant presented her with a choice, saying, “It is no longer appropriate for you to remain with us in this fashion.” She would either have to become his sabaya or be married off. “What about going back to my family?” she asked. “You are a Muslim now. If you go back you will be a kuffar and go to hell,” he responded, using the Islamic term for “infidel.” Sipan took a gamble and picked marriage.

In January 2017, she was handed to Abu Azam Lubnani, a 22 year-old Lebanese IS fighter and a close associate of Adnani’s personal bodyguard who was killed along with her previous tormentor. “They gave me to him for free. I was devastated but I knew that for me now this was the reality and that I must accept it.”

Lubnani married her in an Islamic ceremony. He had no other wives or sabayas. “He was tall, muscular and had long, dirty blond hair. He treated me kindly, coming back home every night.”

She asked for her family. Lubnani tracked down Majdal in a military camp in Al Rai and brought him to their apartment for a three-day visit. “We can say that Lubnani loved her. He was treating her well,” Majdal recalled. But Sipan was pale and listless. “If you see our family again, tell them I died. Tell them to make a grave for me,” Sipan said. Majdal refused.

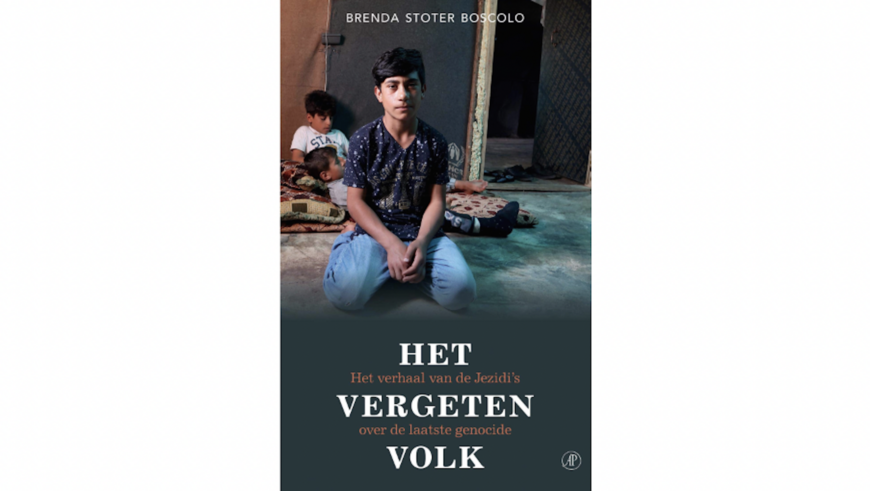

Roughly two months later, Majdal managed to escape, making his way back to Dohuk in Iraqi Kurdistan, where tens of thousands of Yazidis were living in displacement camps. His story appears in a book about the Yazidi genocide by Dutch journalist Brenda Stoter Boscolo titled, “The Forgotten People.” Majdal is featured on its cover.

In his debriefing with Iraqi Kurdish security officials, Majdal described where his sister was living. Coalition officials were in the room, he said. “They pulled out a map and asked me to describe her exact whereabouts.” Majdal did.

Soon after, coalition warplanes struck the building. “I now realize they weren’t interested in rescuing my sister. They wanted to get Lubnani,” Majdal said. But Lubnani wasn’t home. The building collapsed in a heap of rubble with Sipan buried underneath.

Rescue workers took her for dead and tossed her body on a pile of corpses. Once again fate intervened when nurse who was helping bury the dead noticed that Sipan was unconscious but breathing still. He rushed her to a hospital. She had an enormous gash across her belly and was soaked in blood.

"The Forgotten People," a book on the Yazidi genocide by Brenda Stoter Boscolo, featuring Majdal on the cover. (De Arbeiderspers)

Sipan spent three months in the hospital, drifting in and out of consciousness. The nurse had made it his mission to ensure her survival. “He never left my side. He kept asking me who I was. I said nothing. I hoped to recover and run away.” But her wound became infected. She was weak and dizzy, “unable to even drink a glass of water on my own.” Escape was not an option.

The nurse had meanwhile been making enquiries. Lubnani showed up at her bedside one day and her heart sank. Soon after he took her to his new lodgings. But the coalition campaign to retake Raqqa had started in earnest. It was time to get out.

For roughly a year, they moved from one safe house to another starting in al-Bukamal on the Iraqi border, moving on to Hajin, Al-Hasakah and finally Deir ez-Zor. Sipan had not fully recovered and was in constant pain as she carried more than a suitcase with her. She was expecting a child. He had wanted a baby. She did not. “I wished to die after hearing this because I did not want to have a child who will bear the name of a terrorist father.”

Seven months into her pregnancy, her injury grew worse and she was spirited to a nearby hospital with a fake identity for an emergency cesarean section. It was a boy. “I named him Khalil,” she said, losing her composure for the first time.

Lubnani was overjoyed. He decided it was time to head back home to Lebanon to raise their child. Arrangements were made with a smuggler and they set off in a car. With the smuggler at the wheel, they headed across the Syrian desert, in a southwesterly direction toward the Lebanese border. They used a dirt track the smuggler assured them was safe. Another car carrying IS militants had taken the same road the day before and had made it to Lebanon intact.

Lubnani sat in the front with the smuggler. Sipan sat in the back cradling three-month old Khalil in her arms. She had nodded off when “suddenly there was a loud explosion and the car literally flew in the air.” They had hit a land mine. Flames leapt from the front of the car. A fragment of metal had pierced the infant’s back. He was bleeding but alive. Sipan had cuts on her hands and her face. She pulled the baby to her chest and got out. The smuggler was hanging out of the side of the car, his guts spilling out, one of his legs missing and the other stuck inside the car. Lubnani was badly injured but trying to pull the smuggler out. “The smuggler was barely alive. You could tell he was suffering.” Lubnani took his off his tactical vest and suicide belt and sat on the ground, his legs stretched out before him in a daze. “I sat beside him for an hour weighing what to do.” With the baby parked on her left hip, she lifted herself up, reached for Lubnani’s gun, pointed it at his back and pulled the trigger. He died instantly. She shot the smuggler next in an act of mercy and threw away the gun, swaddled the baby in her abaya and began to walk.

She feels no remorse. Lubnani, “was an evil man, serving a state that was murdering innocent people. He showed me videos of himself lining up prisoners on the ground and shooting them in the back and shouting ‘Allahu Akbar.’ He was very proud of that. If I hadn’t killed them, I would never be free. It was my last chance.”

Sipan had no idea where she was as she wandered around aimlessly in the desert hoping to find shelter. She hugged the baby to her chest. He was bleeding more heavily. Soon she could no longer feel his pulse. “I kept telling myself, ‘He’s going to be OK. He is going to be OK.’” As night drew closer the infant’s body stiffened and went cold. “I slapped his cheeks, trying to bring life back to him,” Sipan said. Tears started rolling down her cheeks for the first time. She brushed them away with her fingers, paused briefly and continued the narrative, or tried. “I dug a hole and buried my baby in the desert,” she said. The tears welled up again. We decided to take a break.

Sipan continued to walk in the desert, utterly numb, and saw what looked like an abandoned barn. “I arrived there and just collapsed.” She was awoken by a splash of water on her face. A middle-aged Bedouin in his sixties was peering down at her. “Wake up, my daughter,” he said. He took Sipan to his tent, which he shared with his wife and two daughters. He was a shepherd. They took her to a hospital in Daraa, the southwestern city now back under the regime’s control where the uprising initially began in 2011. “It must have been October,” she said.

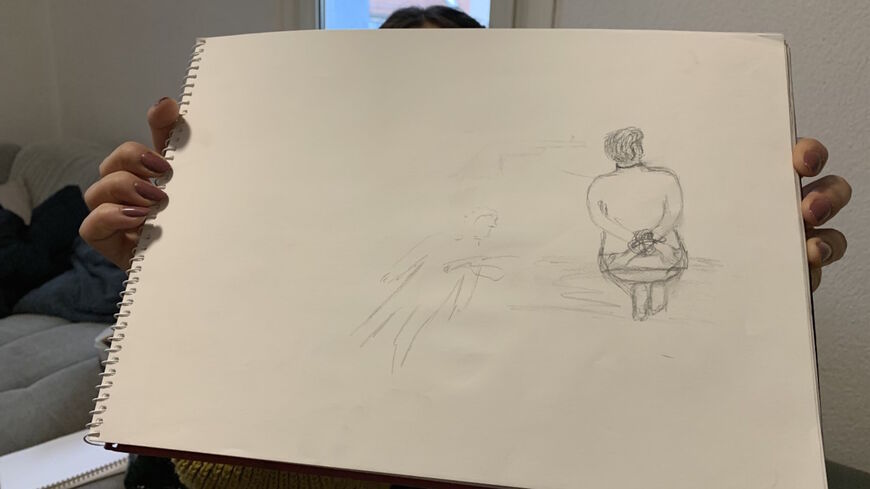

A sketch by Sipan Ajo in Rottweil, Germany, Feb. 18, 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

For almost two years, Sipan lived with the Bedouins, helping them tend their sheep and grow some vegetables in the Syrian badiya, or desert. The routine was calming and she began to regain her strength. Once she was sure that they were not connected to the Islamic State, she told them her story. The farmer, however, refused to let her use his phone. He was worried it might be monitored by the authorities and that he would get in trouble, or that her family would accuse him of kidnapping her. However, he paid her for her work and by July 2021, Sipan had saved enough money to buy her own mobile phone, a secondhand Samsung J1.

She created a Facebook account with a fake male identity, “Osama,” and began searching for Yazidi accounts. She came up with one Talal Yazidi and decided to reach out to him, asking if he knew any of her brothers. He gave her Majdal’s number. She texted Majdal on WhatsApp, asking, “Where is your sister, Sipan?” Majdal responded, “She is dead. She died four years ago.”

Sipan texted him again. “Are you sure she is dead.” He replied that he was. The family had heard of the coalition airstrike on the building where she lived with Lubnani in Raqqa and assumed she was dead. “What if I provide you with information about your sister, what will you give me?” she asked. “Everything you want,” he responded. This time she called him with the video switched on. “At first he didn’t recognize me. He was shocked,” Sipan said.

Soon the miraculous news reached her five sisters and three other surviving brothers — as well as her mother, who she was shocked to learn was still alive. Money exchanged hands, a smuggler was found and the Bedouins drove Sipan to Damascus, where the smuggler picked her up and drove her back across the desert to Al-Hasakah, which was under the control of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces. There she was entrusted to a Yazidi organization that dealt with such cases, given fresh clothes and taken to the border a week later. After several attempts — border guards kept turning her back because she had no papers — she managed to cross with the help of Kocho’s mukhtar Naif Jasso, who appealed for their mercy. Two of her brothers were there to greet her. It’s the one date she remembers very clearly: Aug. 2, 2021, “the day I became free.”

The siblings headed for Dohuk, where she was debriefed much like Majdal by Iraqi Kurdish security officials, with Americans in the room. “They showed me an album full of pictures of Islamic State leaders and asked, ‘Do you recognize any?’” One of the photos she recognized was of Abu Ibrahim al-Qurayshi, the Iraqi who became IS leader in 2019 following the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Both men were killed in US military operations near the Turkish border in Syria. She had seen Qurayshi at a safe house in al-Bukamal and overheard him saying that he would be going to Idlib. “I told the Americans that. But they didn’t ask me too many details,” she said.

Sipan also recognized a photo of of Baghdad's first wife, Asma Fawzi Muhammad Al-Qubaysi, who was caught by Turkey in the border province of Hatay in 2018. “Yes, that’s Um Khaled,” she said when shown a head shot of the woman carried in a news story of her arrest.

A photo of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's wife after her capture by Turkish authorities. (handout from Turkish security officials)

Sipan returned to a changed world. Most of her people were living in squalid and overpopulated displacement camps. Her mother, who was freed with her youngest brother, Nechirvan, in a prisoner exchange, had been accepted along with one other brother and her two unmarried sisters by Germany’s Baden-Wurttemburg state, part of a program launched in 2015 to resettle the most vulnerable and traumatized Yazidi refugees. They came to Rottweil.

Her remaining brother and two sisters were all married and had not been held captive by IS, and therefore did not qualify. And Majdal had not escaped in time. Sipan settled into the camp in Iraqi Kurdistan with them.

The early days were hard. “Some of the people were taunting and bullying me, saying I had stayed seven years in Syria because I ‘agreed with them.’”

On Aug. 15, Sipan made her first visit to Kocho to visit the symbolic grave her family had erected for her. “When I saw the grave, it was a big shock. For a moment I thought I was actually dead. That is when I really began to come back to life. It gave me the courage to move on.”

Sipan began attending sessions at a support group for Yazidi survivors. “I enjoyed spending time with them because they understood me,” she said. “I didn’t feel judged.” She learned how to sew and to bake cakes and went on excursions. The process of healing was just starting when in November, news came from Germany that her mother was gravely ill. She knew that her family was withholding the truth: Her mother was dead. Sipan was devastated. She needed to see her mother before she was buried, one last time. She rushed to the German Consulate in Erbil to apply for a visa only to be turned away by security guards.

Ever resourceful, Sipan filmed a video of herself outside the consulate building appealing for help. The video went viral. She and Majdal were issued visas and arrived in time for her mother’s funeral on Nov. 17. They are now in Rottweil waiting for their asylum applications to be processed.

Sipan still has nightmares. “I see men raping me and that night in the school in Kocho. I also see my baby,” she said in a lowered voice. Did she have any pictures of him? No.

Sipan Ajo visits her mother's grave in Rottweil, Germany, Feb. 18, 2022. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Jan Kizilhan, an ethnic Yazidi psychologist, helped select some 1,100 Yazidi women and children for the Bad Wurttemburg resettlement scheme. He says he personally examined some 1,403 women enslaved by the jihadis in 2015 and was the first to describe his people’s plight as a genocide.

Kizilhan is currently dean at the Institute of Psychotherapy and Psycho-traumatology at University of Duhok, which he pioneered. He doubles as director of the Institute for Transcultural Health Science at the State University of Baden-Württemberg.

“When you thought you had already heard everything like the execution of their husbands, fathers, brothers in front of their eyes, the sale at slave markets and mass rape, torture and starvation, there came women and children who recounted even worse,” he told Al-Monitor in an interview in Stuttgart.

The women have flashbacks, nightmares and “experience profound shame and feelings of humiliation and being abandoned by the world,” Kizilhan said. They also remember the stories of their ancestors who were slaughtered in the 74 previous genocides carried out against the Yazidis over the past 800 years.The good news is that their rehabilitation in Germany, already home to over 200,000 Yazidis, has proved very successful. “More than 40 young women have married and had children. There has not been a single case of suicide so far,” Kizilhan noted, whereas in the camps numerous suicides have been reported and continue to occur.

Sipan seems well adjusted to her new life with her siblings. “I am their mother now.”

She wants to resume her education. “I was the top student in my class.” And she has no intention of blotting out the past. She’s writing a memoir and hopes it will be published “to inspire other women and girls.”

Sipan does not idealize her previous life in Kocho. “Life was difficult. We were poor and discriminated against. Our Muslim neighbors betrayed us. The peshmerga abandoned us. My life is better here,” she said.

For all her bravura, it’s clear Sipan still suffers and mourns the loss of her child. She shows us a sketchbook filled with her drawings. One is of a young girl with long hair. Her face is asymmetrical. One half is happy, the other sad.