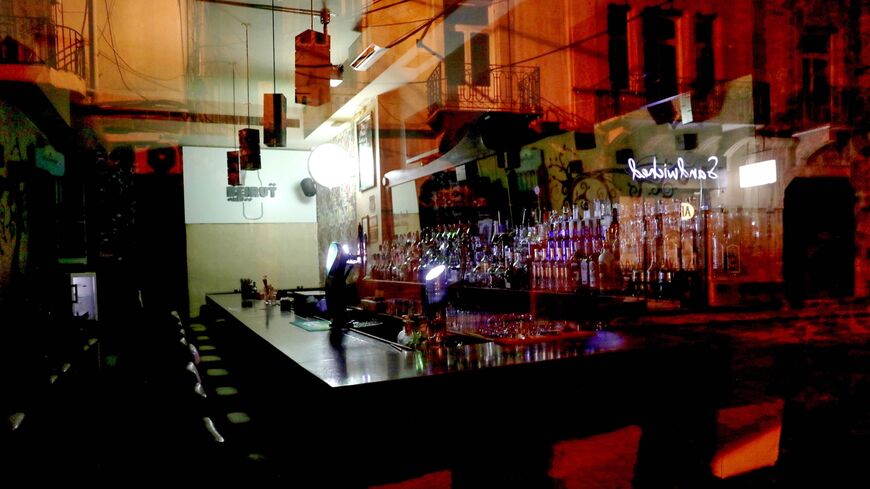

BEIRUT — In the early afternoon along Armenia Street in Mar Mikhael, one of Beirut’s vibrant nightlife hubs, bar staff set up for the long night ahead. While some turned chairs, others prepped the bar and unpacked boxes of Christmas decorations for the much-anticipated holiday business.

“A lot of Lebanese come back for the holidays and they come with fresh dollars, so they end up spending a lot of money,” says Mark Hayek, a bartender at Internazionale Bar, one of the first to open along the street.

Flights to Lebanon between Dec. 20 and 31 reached 85% capacity by November, according to the president of Lebanon’s Association and Travel and Tourist Agents, Jean Abboud. L'Orient quoted him as saying they would likely reach 100% capacity and more flights would be organized as the country welcomes hundreds of thousands of Lebanese expatriates and tourists this holiday season.

Tourism revenues are expected to be similar to those seen over the summer, which counted over one million visitors who brought in nearly $4.5 million in revenue, Abboud noted, saying, there would be a “significant increase” in Arab and foreign tourists, a rebound from the past three winters when protests, the pandemic and the port explosion had deterred visitors.

This is excellent news for Lebanon’s restaurant and service sector, which has been hard hit by one of the world’s worst economic crises. The Lebanese pound has depreciated by more than 95% in the three years since the country fell into crisis. The average income in Lebanon has dropped by about 40% and amid the severe depreciation and triple-digit inflation, the country’s residents have lost over 90% of their purchasing power, according to a report by the American University of Beirut.

The drastic decline in disposable income, combined with the pandemic-induced closures, forced 784 restaurants to shut down between September 2019 and February 2020. Nearly half of workers in the service sector have lost their jobs since the beginning of the crisis in 2019, with a quarter of workers reporting substantially reduced income.

But though heavily impacted by the crisis, nightlife in Lebanon has managed to survive. “There’s always been a nice nightlife,” Hayek told Al-Monitor, “but before 2019, it definitely felt different.”

At Bodo, a bar less than a minute's walk from Internazionale, employees adorned the walls with festive garlands and wreaths. But the bar’s manager, Ahmad Daouk, is less optimistic about the business the season may bring.

“The economic situation has doomed everything,” he told Al-Monitor, noting his low hopes for relief from holiday travelers.

“We’re not making money,” Daouk said. “Prices are expensive, but if you divide them by dollars, you’ll see that you pay nothing,” he added, explaining that bars and restaurants still purchase alcohol at dollar rates, but then have to sell it at a rate Lebanese will buy, which is now significantly less.

Daouk noted that the salaries for those who work in the service sector have not been adjusted for the high inflation.

Leila Dagher, an economics professor at the American University of Beirut and the lead author of the report on the impact of the crisis, told Al-Monitor that 78.2% of people working in the hospitality sector indicated a wish to immigrate — the second-highest percentage among the seven sectors investigated.

“All employees are going to quit,” Daouk stated. “How to live? How to pay?”

Since 2019, over 200,000 people have immigrated from Lebanon, a 40% increase from the four years before the crisis, said Dagher, citing Information International.

But many of the Lebanese expatriates who now live abroad return over the holidays to visit relatives and friends, often bringing with them dollars and vigor to experience the country, ramping up business for the struggling restaurant and hospitality sector.

Like many others, Loulwa Kalassina will return to the country for the holidays. Kalassina now studies in Ankara, Turkey, and visits Lebanon twice a year, she told Al-Monitor. “When I go back, I plan to meet friends and family,” she said. “We go to restaurants, we go to festivals — a club event or bars in Beirut.”

Down the street from Internazionale and Bodo is Fuego, another bar among the dozens on Armenia Street. Fuego’s bar manager, Thierry Haje, said that business might get better soon with the upcoming holidays. He noted that the street is more popular in the winter, especially for Christmas and the new year. The coastal towns with their beach clubs and rooftop bars normally draw in more business over the summer.

Lebanon’s New Year celebrations are known around the world, with a host of Lebanese expatriates and tourists coming to celebrate. And now with the depreciation of the lira, those bringing dollars from abroad can celebrate more cheaply, another factor now drawing in the crowds.

Haje said that while many the clubs in Lebanon have closed over the last three years of crisis, “more are opening every day,” though they cannot afford the big-name entertainers they used to.