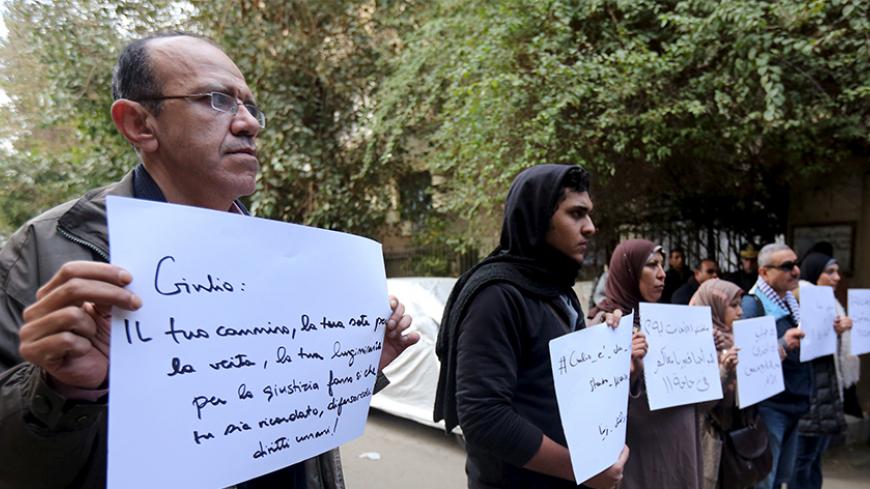

The mood was somber as dozens of Egyptian activists, academics and foreign journalists gathered outside the Italian Embassy in Cairo on the afternoon of Feb. 6 to pay respects to slain Italian doctoral student Giulio Regeni.

There was a heavy security presence in the small area that had been cordoned off by the police for the silent vigil. Security officers, many in plainclothes, watched nervously as the mourners laid wreaths and lit candles as a tribute to the 28-year-old researcher whose brutal killing sent shock waves across Egypt and the world.

“The Egyptian regime clearly does not want any witnesses to the atrocities committed by the security forces against government critics on a near-daily basis,” said Angela, an Italian writer and researcher who wanted to be identified only by her first name for reasons of personal safety. She added that foreign journalists and researchers, in particular, were no longer welcome in Egypt “as they are the ones who document the abuses.”

Angela, who has lived in Egypt for the last four years, told Al-Monitor that it was becoming increasingly difficult for her to do her work.

“I am particularly worried about the safety of my Egyptian colleagues. They are the ones most at risk,” she lamented.

An Egyptian activist standing behind Angela raised a sign reading, “Why kill foreigners? Aren’t we enough for you?”

Another held a placard with the message, “Those who killed Giulio are the same murderers who kill Egyptians.”

The messages in English, Arabic and Italian suggested that the security forces were behind Regeni’s death. The Egyptian authorities had stepped up a crackdown on dissent in the weeks leading up to Jan. 25, the day marking the fifth anniversary of the uprising that toppled President Hosni Mubarak. Hundreds of apartments in downtown Cairo were raided by the police, and several “suspects” were arrested and later charged with “inciting protests.” Rights groups and opposition activists accuse the security forces of detaining hundreds of activists without reporting their arrests, citing at least 340 cases of forced disappearances within a span of four months (August to November 2015). El Nadeem Centre for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence, an Egyptian rights group, recently published a report saying there were 66 cases of forced disappearances just last month. Meanwhile, the International Federation for Human Rights, a coalition of 178 nongovernmental organizations, said in a report published to coincide with the anniversary of the 2011 uprising, “Five years on, Egypt is witnessing an unprecedented deterioration in the status of human rights in its modern history.” According to the movement, at least 41,000 people have been detained, charged or sentenced since July 2013, when Islamist President Mohammed Morsi was overthrown by the military following mass protests.

Regeni mysteriously disappeared Jan. 25, prompting an online campaign to bring attention to his case by worried colleagues and activists who used the hashtag #WhereIsGiulio? He was last seen at a metro station near his home in Cairo’s Dokki neighborhood and had reportedly been heading to meet a friend in a downtown cafe. His badly mutilated body was found on the side of a highway on the outskirts of Cairo on Feb. 3, nine days after his disappearance. Naked from the waist down, the body showed clear signs of torture, including cigarette burns, bruises and multiple stab wounds, leading the senior prosecutor for the Giza district to conclude that he had “died a slow and painful death.” Angelino Alfano, the Italian interior minister, confirmed the claim after a second autopsy was conducted in Italy. Alfano told Italian media that Regeni appeared to have suffered. Alfano told Italian media that Regeni appeared to have suffered “an inhuman, animal-like violence before his death.”

Some Italian media suggested that the fact that Regeni had had his nails pulled out indicates he may have been suspected by Egyptian security forces of being a spy, and hence, “worthy of such inhumane treatment.”

Egypt has witnessed a surge in xenophobia since the 2011 uprising with Egyptian media often warning against “foreigners seeking to foment unrest.” The media has also been rife with conspiracy theories of “foreign powers seeking to destroy the nation.” The oft-repeated statements by some state officials and government loyalists in the media have prompted mob attacks on several foreign journalists. In recent weeks, an American who had been studying Arabic in Cairo was taken into police custody after informants reported him to the police for allegedly inciting protests. He had been having a discussion with some Egyptian young people in a downtown Cairo cafe. He was later deported.

The authorities have also been particularly wary of researchers: Ismail Eskandarani, a researcher who specialized in Sinai affairs, was arrested at the airport on his arrival in Hurghada on Dec. 1, and has since been charged with belonging to an outlawed group and spreading misinformation to tarnish Egypt’s image. Atef Boutros, an Egyptian-German researcher, was last month barred entry into the country by airport security on grounds that he was a “threat to national security.” Regeni’s research had focused on labor movements, a sensitive topic to the authorities: The 2008 labor strikes in Mehalla were believed to have been the first spark of the mass uprising that erupted three years later. He had reportedly been in touch with trade unionists and opposition activists.

While Egyptian activists, Islamists and the Italian media support the argument that police may have had a role in Regeni’s death, Egyptian government officials and regime supporters offer an alternative narrative. At a press conference Feb. 8, Egypt’s Interior Minister Magdi Abdel Ghaffar rejected the accusations against the police, saying that “such rumors are unacceptable.”

“This is not our policy,” he said. “Egyptian security agencies are known for their integrity and transparency.” He suggested that a criminal act may have caused Regeni’s death. Earlier, some Egyptian media quoted another police source — the head of investigations at the Giza police department — as saying that Regeni had most likely died in a car accident and that no foul play was suspected.

While it may be best for all parties to refrain from speculating who the likely killers may be — at least until the results of the investigation are announced — Regeni’s friends in Cairo worry that they may never know for certain who was responsible for his death.

A friend of Regeni's told Al-Monitor on condition of anonymity, "We have seen on several occasions security officials reluctant to reveal truths that they believe may be damaging to the country's reputation. Nothing can tarnish Egypt’s image more than lack of transparency. Any attempts to withhold facts or hide truths may cause Egypt to lose a valuable ally [Italy]," she warned.

Another friend agreed, saying, "What we need right now is to strengthen confidence between the people and the authorities.”