The Gulf Arabs recognize a strategic reality that has eluded the stove-piped US foreign and security policy bureaucracy for too long: The Horn of Africa is an integral part of the Middle East’s security landscape, and increasingly so. No country demonstrates this more clearly than Ethiopia. That country’s escalating internal crises pose an increasingly grave threat not only to the country’s citizens but to international peace and security and to the interests of the United States and its partners in the Middle East, principally Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

As a recent bipartisan study group convened by the US Institute of Peace (USIP) concluded, developments in the Horn of Africa are not only shaped by the states of the Middle East “but also have a direct impact on [these states’] political, economic, and security environments.” Ethiopia’s internal and external borders are being changed violently, and the centrifugal forces of nationalism that now dominate Ethiopian politics are indicative of the weakness of the central state, not the strength of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed or the federal government. These intrastate fissures are undermining the country’s territorial integrity and morphing into interstate conflicts involving, to date, Eritrea and Sudan.

The armed confrontation that erupted Nov. 3 between the federal government and the regional government in Tigray state precipitated what Abiy characterized as a “domestic law enforcement operation.” The involvement of Eritrean combat forces, however, as well as the federal government’s use of airstrikes, mechanized ground units and ethnic militias undermines the credibility of that characterization. Similarly, assertions that the operation has succeeded in stabilizing Tigray is belied by the persistent violence in the region; a worsening humanitarian emergency; the government’s unwillingness to allow adequate access for a humanitarian response; and reports of severe human rights abuses, including of Eritrean refugees in Tigray being killed or forcibly returned to Eritrea.

The war in Tigray is symptomatic of a national political crisis in Ethiopia, which preceded Nov. 3 but has been exacerbated by the nationalist rivalries that have been unleashed since then. Much of western Tigray may now be occupied by Amhara regional state forces, and a border war has erupted between Amhara militias and the Sudanese military. Ethnically motivated killings of Amhara, Oromo and others in Benishangul-Gumuz regional state have precipitated the intervention of Amhara security forces, an unprecedented military deployment by one of Ethiopia’s states into another. In addition, the federal government has been engaged in an intensifying campaign against insurgents in Oromia regional state for months. While each of these conflicts involve historic and complex claims over territory, resources, identity and political representation, the pursuit of those claims by force of arms has set the country on a trajectory toward fragmentation.

The fallout for the states of the Middle East is significant.

First, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have both made considerable political and economic investments in the leadership in Addis Ababa, Cairo and Khartoum, investments that will be undermined by bourgeoning conflict among the three. Egyptian-Ethiopian relations have long been strained by the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), and Ethiopian-Sudanese relations have become increasingly toxic due not only to the GERD but to the border conflict. The recent spike in violence in Benishangul-Gumuz, where the dam is located, could also pose a threat to the control and function of the dam itself. The Nile is an emotive and sensitive issue in Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan, and the crisis facing Abiy’s government makes any realistic compromise even more difficult.

Second, Ethiopia’s fragmentation could portend displacement on a scale not seen in modern times. In 2018-19, approximately 300,000 people — the vast majority of whom were Ethiopian and Eritrean — fled the Horn of Africa for Yemen, in spite of that country’s civil war. As the USIP senior study group report warned, the breakdown of Ethiopia — a country of over 110 million people — would “result in a refugee crisis that could easily dwarf that figure.” Over 56,000 refugees have already fled from Tigray into Sudan since November. Large-scale refugee outflows could destabilize Sudan’s delicate transition, and the consequences of state collapse in Ethiopia would also certainly extend across the Red Sea.

Third, calls for the secession of one or more of Ethiopia’s states are gaining steam, which would put additional strain on the already fraying state system in the Middle East, wracked as it is by the ongoing wars in Libya, Syria and Yemen. Somewhat unique among world regions, the Horn of Africa has several recent experiences with secession — Eritrea from Ethiopia in 1993, South Sudan from Sudan in 2011 and the self-declared independence of Somaliland from Somalia in 2001. The prospects and ramifications of further changes to the regional order should not be underestimated.

Fourth, the risk of radicalization is real should extremist groups exploit the political and security crises inside Ethiopia, particularly if Abiy and his supporters continue to reject dialogue as a means of channeling political grievance. For example, al-Shabab, the Islamic State or al-Qaeda could play for advantage inside Ethiopia’s Somali region or among disaffected and disenfranchised Muslim communities in Oromia and elsewhere.

Brute force is no more likely to be successful in Ethiopia than it has been in Syria in preserving the integrity of the state or in mitigating threats to its neighbors or to the states of the Middle East. Nor can elections that Abiy has announced for June be credible, free or fair in the current political and security climate and therefore able to reconcile the competing visions for the country’s future. The political transitions that have unfolded in Ethiopia and Sudan in the last two years in fact illustrate that the restive and youthful body politics of the Horn of Africa are too diverse, pluralistic and eager for political change for authoritarian repression to result in stability.

Ethiopia’s recent history provides a sobering precedent. In 2015-16, large-scale protests against Ethiopia’s federal government, which was then dominated by Tigray’s ruling party, was met by a military crackdown that both failed to quell the unrest and led to expanding violence. The widening political and security catastrophe only abated with the resignation of former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, the promise of a new political dispensation heralded by Abiy’s accession to the premiership and his articulation of a reform agenda that included a loosening of restrictions on civic space and the prospect of a more inclusive political discourse.

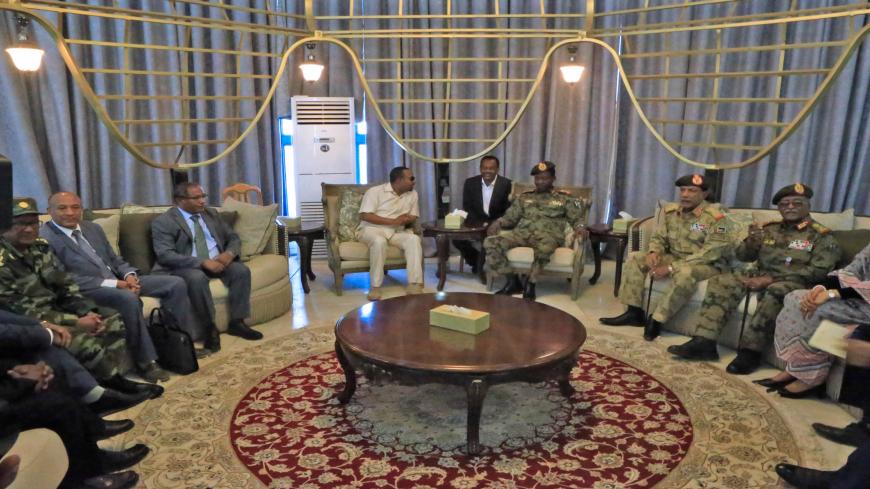

Similarly, when a junta deposed Omar al-Bashir following months of nationwide protests in Sudan, there were those within the security services and among their supporters abroad who argued that stability could be achieved through military rule. This proved elusive, however, amid the massacre of protesters at a sit-in in Khartoum and continued mass demonstrations demanding civilian rule. Following talks between the junta and the umbrella group representing the protesters, an agreement was reached to form a transitional government based on a cohabitation arrangement between a civilian-led Cabinet and a council chaired by the military until elections in 2022 — an agreement due, in part, to diplomatic coordination between the United States and the Gulf. While fragile, this negotiated arrangement has so far averted fears of a slide into civil war akin to that of Libya, and Sudan is now a more responsible member of the international community than it has been at any time in the last three decades.

The Gulf states’ policies toward the Horn of Africa are undoubtedly rooted in their own strategic and political calculations. They understand that the two sides of the Red Sea comprise an integrated region that transcends the geographic distinctions between Africa and the Middle East. The close bilateral relationships that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have cultivated with Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, alongside Abu Dhabi’s historic ties with Asmara, can be strong assets in stabilizing the Horn of Africa in the long term. The long-awaited reconciliation among the Gulf Cooperation Council countries could also alleviate competitive pressures in Somalia, where Qatar has supported the federal government and the UAE has backed the federal member states.

US-Gulf coordination is needed most urgently, however, in the case of Ethiopia. The Gulf states’ explicit or implicit support for Abiy’s shortsighted approach or for Eritrean military intervention not only risks implicating the Gulf in the humanitarian emergency in Tigray but damaging their own strategic interests as the Ethiopian state deteriorates. While Abiy and the federal government continue to prejudice military action over dialogue — not just with Tigrayan leaders but across the political spectrum — there is an urgent need for a process that provides an opportunity to build a new national consensus in Ethiopia, including an understanding of the electoral calendar. The United States and its Gulf partners must cooperate in promoting and supporting such an effort.