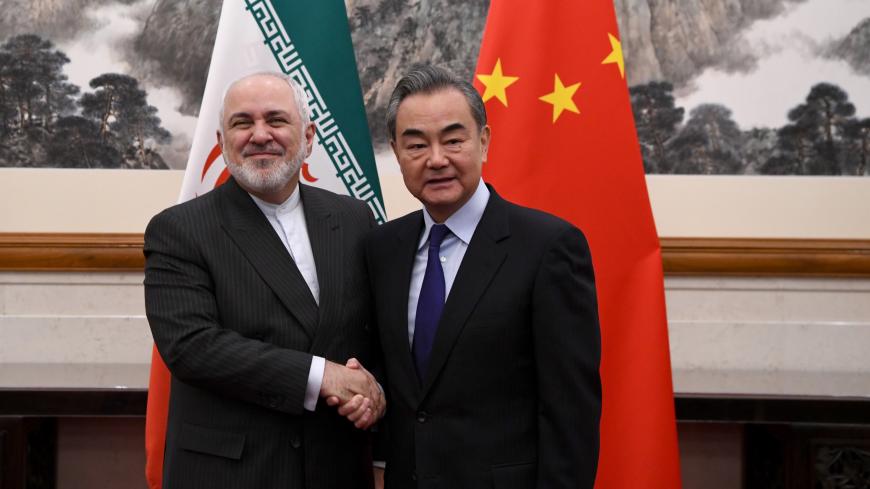

“There is nothing to hide about the deal. Every stage has been transparent, and once it is finalized, the details will be made public,” Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif told lawmakers last week as he was grilled over a controversial 25-year partnership deal with China. “The point that has to be taken into consideration in our foreign policy is the shift in global power,” Zarif argued in justification of the pact.

According to Iranian officials, the draft of the road map, known as the Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, was approved by the administration of President Hassan Rouhani in June. The detailed content, however, remains open to heated debate and speculation. While the draft was in the works for over four years, it received little attention until some media reported about what they claimed were key facts and figures involved.

In September 2019, Petroleum Economist, relying on an unnamed source within Iran’s Oil Ministry, detailed a $400 billion Chinese investment under the deal in Iran’s oil, gas and transport sectors, with Beijing enjoying a 32% discount in crude purchases along with two-year payment breaks. The partnership pact, other reports say, will also grant the Chinese government a significant presence in a wide variety of other projects from security and telecom infrastructure to health and tourism.

What has particularly drawn the ire of opponents at home are claims that the plan will give China permission to dispatch up to 5,000 troops to protect its interests in Iran as well as significant control over Iranian islands in the country’s southern business hubs.

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, known for his populistic approach toward governance, was among the first to bring the debate into the public sphere. Ahmadinejad criticized the Rouhani government for “secretly signing a deal” with a foreign state. “Any such accord that counters the people’s will and national interests lacks validity and will not be recognized by the Iranian nation,” he warned, suggesting that it also violated the fundamental principles of the Islamic Revolution that were meant to “withhold nothing from the nation.”

In reaction, Iranian officials have come out one after another with general explanations and at times stinging attacks against critics. Foreign Ministry spokesman Abbas Mousavi said some speculation about the deal is “not even worth denying.” He said the government's refusal to publicly offer details is meant to avert attempts by rival states who seek to sabotage and derail the talks. He described the road map as a win-win deal, which will help Iran, “a big power in West Asia,” and “China, a soon-to-be global leading economy,” to resist “traditional bullies more powerfully than before.” Mousavi dismissed the allegations of a Chinese military presence and island control as “illusion” and “misinformation.”

Following the 2018 US departure from the Iran nuclear deal — the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) — and with the Donald Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy in full force, Iran’s leadership has scrambled to absorb the economic shock and mitigate the impacts through an eastward turn in its economic diplomacy. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has openly promoted the new approach, vigorously pursued by the country’s Foreign Ministry.

But the foundations of the Iran-China partnership agreement are believed to have been laid during a visit by China’s President Xi Jinping to Tehran and his one-on-one meeting with Ayatollah Khamenei in January 2016, only a week after the start of the JCPOA’s implementation. “The agreement on a 25-year strategic relationship is prudent and wise,” the Iranian supreme leader told the Chinese president.

Since the 1979 revolution, self-reliance and independence from Western and Eastern powers have served as a basic tenet of the Islamic Republic’s diplomacy, manifested in the tiled sign that reads “no to East, no to West” at the entrance of the Foreign Ministry in central Tehran. The same is now forming much of the counter-argument against the Iran-China deal. But the government has its own explanations. “Basically, there is no such dichotomy as West and East in our foreign policy. The Islamic Republic is not restricting itself to either side. We are ready for similar accords with any country based on mutual trust,” said government spokesman Ali Rabiee.

Still, none of those statements seem to have convinced opponents who seek to rest assured that the deal does not make Iran a “Chinese colony,” as they cite examples of several African countries whose economies has fallen under increasing Chinese influence in the past decade. “It could be yet another Treaty of Turkmenchay,” other critics have also argued, referencing a 19th century agreement under which Iran had to cede significant swaths of its territory to the Russian empire.

On the claims that China will dominate Iranian islands, the ultraconservative Tasnim News Agency said the draft only talks about development of tourism and fisheries in selected islands. And in a statement, the Secretariat of the Supreme Council of Iranian Special and Free Zones categorically denied any handover of Iranian islands, linking the claims to individuals working for “foreign adversaries.” In recent months, reports have come out on massive “nighttime fishing” in Iran’s southern waters by Chinese boats.

The chief of the presidential staff, Mahmoud Vaezi, known as Rouhani’s right-hand man, also described the line of criticism as “lies that are spread” by individuals linked to certain foreign states. He reassured the public that the partnership plan will not be signed without approval from parliament.

How much backing the plan will receive in parliament remains hard to precisely predict, as mixed signals continue to be sent out from different lawmakers. Mohammad Reza Sabaghian, a member of the parliament's Presiding Board, called for closer oversight of the Iran-China negotiations, calling the plan Zarif's “recipe.” Sabaghian promised that parliamentarians will not allow a repeat of the “bitter experience” of the JCPOA and unlike the nuclear deal, they will refuse to “swallow” the China partnership deal. The lawmaker was alluding to the quick approval process of the nuclear accord in 2015, when the Iranian parliament was said to have been required by the supreme leader to fast-track the process.

But signs that the deal may have an easy path could be read from media outlets at both ends of the spectrum and in their unanimous expressions of support for the “the plan that could be the bright road map for bilateral ties” and attacks against critics, who follow “lies fabricated” about the deal by Western media.

Further negotiations for a final signature on agreement may stretch well into the administration of Rouhani’s successor. Yet regardless of who takes office and how loud the criticism turns, with the go-ahead already issued by the supreme leader — the man with the ultimate say in vital foreign policy decisions — and a parliament packed with his loyalists, the Iran-China partnership deal is unlikely to face any bump on the road toward ratification.