France is increasingly flexing its diplomatic muscles in Iraq as French President Emmanuel Macron hosted the Kurdistan Regional Government's Prime Minister Masrour Barzani last Thursday, only weeks after meeting Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed al-Sudani.

During the meeting, Macron expressed support for Iraq and the KRG in the face of external and domestic security threats, while Barzani lauded Paris as an “ally with a common vision.” Both leaders discussed investments and economic diversification in sectors like agriculture and pledged to further strengthen bilateral cooperation.

France has maneuvered to rival Washington as Baghdad’s primary Western partner and to counterbalance China’s financial and geopolitical influence in the country.

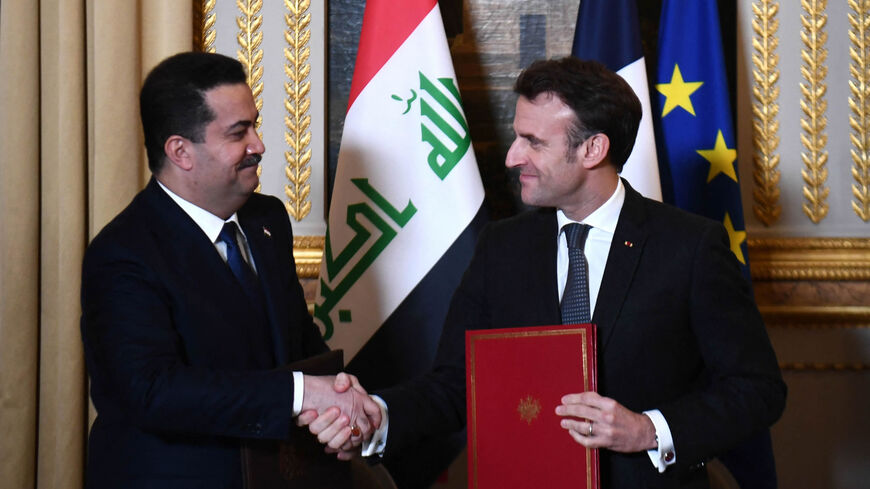

The Macron-Sudani meeting at the end of January laid the groundwork for a strategic partnership. Although it shows Paris’ desire to revive its geopolitical clout in the Middle East and boost its soft power in Iraq, the partnership’s stated aims are to establish a formal and permanent framework for bilateral cooperation in various fields, according to a statement by the Elysee Palace.

As both leaders lauded Paris’ ongoing construction of a medical facility in Sinjar, a commitment was made to continue supporting the Iraqi health care system beyond the meeting. In response to environmental concerns, they also pledged to lessen the impact of climate change there.

Paris has worked to increase its influence in Iraq with other soft power efforts including cultural initiatives such as the Baghdad-based French Institute that teaches French to Iraqi students.

France offered additional investments in Iraqi infrastructure and energy, including green energy projects. Along with the $27 billion September 2021 deal for France’s TotalEnergies to invest in Iraq — a deal that has recently stalled amid disagreements over the shareholding structure — the broader bilateral cooperation grants French companies greater access to Iraqi markets, benefiting France’s economy.

Macron has also positioned himself as a potential security guarantor for Iraq. During the meeting with Sudani, Macron also pledged further support for Iraq’s security infrastructure amid continued extremist threats. France’s role in combating the Islamic State in Iraq had involved Macron’s government providing defensive equipment to Baghdad.

The partnership agreement follows the Baghdad Conference, held in Jordan in December 2022. The summit did not produce tangible results for Iraq’s stability, but did enable Macron to express his vision for the country, calling for an end to foreign intervention and respect for its territorial integrity.

“There is a way that is not … a form of hegemony, imperialism, a model that would be dictated from outside,” said Macron at the regional summit.

Along with its calls to respect Iraq’s sovereignty, Paris recently denounced Iranian militias attacking targets in Iraq, including the airstrikes in the autonomous Kurdistan Region in November 2022. And with China’s expansion into the Middle East and the United States diverting political capital toward the South China Sea along with the war in Ukraine, Paris has an opportunity to act as a buffer against Chinese and Iranian influence in Iraq.

After years of US financial neglect for Iraq’s reconstruction, Beijing has become a dominant economic actor in the country as Baghdad’s largest trading partner, accounting for 44% of Iraq’s oil exports in 2021, and has allocated $10.5 billion for projects including a heavy oil power plant that year.

Following the 2019 “oil for construction” deal, these revenues have helped China contribute to wider infrastructure projects in Iraq — an important country to its Belt and Road Initiative.

Just weeks before Macron hosted Barzani, Beijing also pledged nearly $10 billion in infrastructure projects in the Kurdistan Region, involving sectors like railway networks, power, roads and dams.

Munqith Dagher, senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote about France taking the lead in stopping China's expansion. “It seems that France is spearheading the operation of stopping China’s strategic expansion in order to guard Western economic interests in the region,” he argued in one of his reports on the center's website.

After the United States announced in August 2021 it would withdraw most of its combat troops from Iraq by the end of the year, Macron declared that French troops would not leave the nation. The Washington still has a military presence in Iraq in an advisory and training role, and Washington is still seen as Iraq's most critical security partner. Sudani told the Wall Street Journal last month that Baghdad supports an "indefinite" US troop presence in Iraq.

But France arguably sees itself as the most qualified Western partner to engage with Iraq, as it does not carry the baggage that the United States does from the invasion in 2003, while the United Kingdom has left the European Union and is focusing more on the Gulf region. Most importantly, Macron has pursued a leadership role within the post-Brexit EU to increase France’s foreign policy role and give the EU a larger diplomatic role in the region, the push for which intensified after Macron’s reelection in April 2022 and the resignation of Angela Merkel as German chancellor.

Macron has also tried to restore France to its past position as the “middle power of global influence,” as former French Foreign Minister Hubert Vedrine once described it. A key part of Macron's desire for French involvement in the Middle East has been based on Charles de Gaulle’s idea that France should not necessarily follow US foreign policy.

Indeed, Paris has sought to act as a mediator between Washington and Tehran during previous US tensions with Iran, while running a parallel strategy to that of Washington. Seeking to offer third way diplomacy, Paris has backed efforts to contain Iran’s nuclear program and regional expansion while adopting a more moderate stance amid negotiations on the 2015 nuclear deal.

Yet as the EU has not engaged in long-term and structural planning toward Iraq and the wider region, Macron’s foreign policy vision faces inevitable drawbacks. The EU’s presence has been negligible, except from a few token initiatives to assist Iraq, such as sending a small observatory mission during past elections.

Joe Macaron, geopolitical analyst and former resident fellow at the Arab Center Washington DC, said in a report that Macron's style is incoherent. “There is no clear and coherent Macron doctrine [in the Middle East]. His pragmatic opportunism and style of personal diplomacy typically make a grand entrance but, later, Macron recalibrates, manages expectations, and cuts losses,” he wrote.

Despite its desire to operate independently of the United States, Paris still has to coordinate with Washington for practical reasons since it only has 800 troops in Iraq. For example, France coordinated with the United States on the Abu Dhabi-based French navy's intercepting of an Iranian shipment of weapons destined for Yemen in January.

Such a move would benefit Washington, as the Biden administration has expressed hope that its European allies, particularly France, would do more to work with the United States in the region to address security concerns and counter US rivals.

Ultimately, given China and Iran’s strengthening ties and the region’s increased polarization because of the Ukraine conflict and Tehran’s warmth toward Russia, France may feel further obliged to align with Washington. And while Baghdad has welcomed Paris’ overtures, it may also struggle to compete with China’s financial prowess and therefore have to settle with being a marginal actor, particularly given the absence of a significant EU presence in the country.