Israel-Lebanon maritime agreement to prompt working relations

Al-Monitor Pro Member

Gerald Kepes

President, Competitive Energy Strategies, LLC

Oct. 14, 2022

US-mediated negotiations, underway for months, appear to have reached a successful end, although formal approvals are needed from the Israeli and Lebanese governments (Israel's cabinet gave preliminary approval this week). Full ratification could still be subject to the political jockeying and machinations of various parties. Israel faces an election on Nov. 1, 2022, and Lebanon’s presidential term ends at the same time with no successor identified.

Powerful political factions within each country are either against the proposed agreement or wish to use its existence against their political opponents. The threat of cross-border violence, ever present, looms in the background. However, the Israeli military-security establishment appear to be in favor of the agreement having secured certain guarantees from the US and the main political force in Lebanon, Hezbollah, has acquiesced to dealing with Israel given the dire condition of the Lebanese economy.

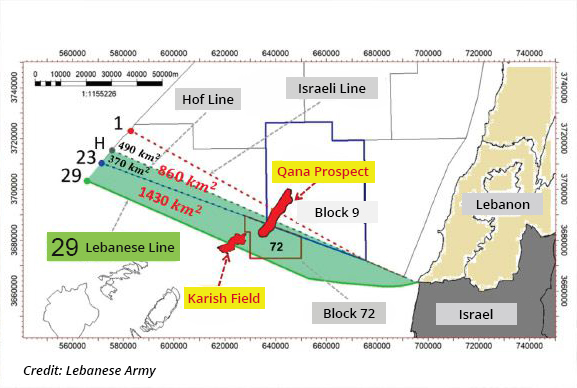

The agreement will recognized the buoy-marked border 3.1 miles off the coast of the northern Israeli city of Rosh Hanikra, then will track Line 23.

- The deepwater area offshore northern Israel and southern Lebanon is located in the Levantine Basin, one of four basins in the world class Eastern Mediterranean natural gas play.

- The discovery and commercial development of the deepwater Tamar and Leviathan gas fields offshore Israel highlighted the potential for additional discoveries in areas northwards which extended into Lebanese waters. The Karish fields (Karish and Karish North) confirmed this potential, but more enticingly suggested that the liquids content of the hydrocarbon potential increased northward also. Producing gas liquids (condensate or even light crude oil) is often more profitable for international oil companies than just producing dry natural gas which unless turned into liquid natural gas (LNG) has to be sold into local markets with complicated pricing terms. The development and then planned streaming of the Karish field gas and liquids boosted the commercial potential for Lebanon’s offshore gas resources but ignited border tensions with Hezbollah.

- The Karish and Karish North gas fields represent 2.6 Tcf of proven and probable natural gas and liquids reserves. The original project schedules called for Karish wet gas (natural gas and liquids) to come onstream in November or December of 2022. Karish North gas and liquids were to come onstream later in 2023.

- Production from the field, operated by Energean, has clearly been delayed due to the uncertain security conditions — Hezbollah sent drones over the Karish field floating production system and had threatened production in the absence of an agreement.

- As a result of the delay of Karish field gas output, Energean may insist that it receive financial compensation given that a declaration of force majeure is a fairly standard clause in a production contract.

- Also, Energean has signed contracts for delivery of gas to selected buyers in Israel. So, there may be penalties accrued given a failure to deliver contracted volumes. Presumably all of this is resolvable given the active participation of the Israeli government, but it is a complication, albeit a second order one.

- The proposed marine border resolution would require two if not three agreements. One between the Lebanese Government and the United States, and a second one signed between the Israeli Government and the United States. This is necessitated by the fact that Israel and Lebanon do not have formal diplomatic relations; technically, the two countries are at war with each other. A third agreement could be made between the two countries and the United Nations which may formally recognize the marine border under international law.

- There are other implications emanating from these agreements which will impact the willingness of foreign oil companies to invest and produce from other regional oil/gas fields. Israel and Cyprus are engaged in “unitization” discussions regarding the Aphrodite gas field reserves which straddle the maritime border between the Republic of Cyprus and Israel, in an area immediately west of the disputed border area between Lebanon and Israel. Unitization agreements are needed to clearly demarcate what portion of the fields are owned by the various parties. Whatever Israel agrees to in its agreement with Lebanon could have an impact on its negotiating position (and outcome) in its unitization discussions with Cyprus.

- TotalEnergies (operator) and Eni are license holders of Block 9, located within Lebanese waters. Block 9 includes the Qana prospect, or at least the portion residing within Lebanese waters. Block 9 has an unassigned equity stake of 20%, formerly held by the Russian company Novatek, which was relinquished earlier in 2022. At some point, this 20% will be awarded to another third party.

- In the absence of a fully ratified marine border agreement (including a revenue sharing agreement for whatever portion of the potential Qana resources resides within Israeli territory), TotalEnergies and Eni will not drill an exploration well, not matter what the potential is.

Scenario 1: One possible scenario, albeit less likely, is that one or both governments fail to ratify the proposed agreement such that talks collapse completely for an extended, unknown period.

One can envision that Karish gas field production would commence with guarantees from the Israeli military, and the full development of the Karish area ensues, including North Karish gas. In parallel the threat level increases with heightened tensions, and attacks, offshore or onshore. At some juncture, Energean could declare force majeure for its entire Karish area development. And other discoveries and potential would not be developed. In this scenario, full development of this portion of Israel’s northern offshore and Lebanon's offshore also would be hindered. If no agreement is reached, TotalEnergies and Eni will not drill an exploration well on the Qana prospect without a marine border agreement.

Scenario 2: A second scenario variously involves the failure to discover commercial resources at the Qana prospect or the failure of unitization negotiations which would follow the discovery of commercial volumes at Qana.

The Qana prospect, the bulk of which appears to lie on the Lebanese side of the border (provisionally) within Block 9, has not been drilled. It looks attractive and is well positioned given the trend established by the Israeli offshore gas fields. It could be substantially larger than the Karish gas fields and, would if successful, probably produce liquids-rich natural gas (wet gas), similar to the Karish gas fields. It is possible that Qana resources could have even higher liquids content and that a commercial discovery could yield hundreds of millions of barrels of condensate and light oil and 5 to 10 Tcf of natural gas. But it is equally (or more) possible that it could be an unsuccessful exploration effort for a variety of technical reasons resulting in a sub-commercial discovery.

Should a Qana discovery be commercial, the next hurdle will be the execution of the terms of reference for a unitization agreement. The revenue sharing (or royalty payments to the Israeli government) would depend on the specific portion of the Qana field reserves lying on the Israeli side of the agreed border. The negotiated terms of reference requires the selection of an internationally recognized, technical consultancy to study the data and then make a final determination of the allocation of reserves between the two governments. If one of the governments does not agree with that determination, they will require and enter into an arbitration mechanism to reach a final agreement. All this takes time.

The unitization agreement/revenue sharing would also include how an Israeli government authority monitors actual production and delivered volumes to the point of sale, pricing and how funds are paid out. This would include both liquids and natural gas reserves and output. In the case of a Qana discovery, the volume of liquids (and therefore value) could be substantial. Assume that Qana field dry gas sold into a Lebanese market (or other) yields $4 per million BTU (mmBritish Thermal Units) to $6 mmBTU. By way of example, Karish gas will receive about $4.30 per mmBTU from the Israeli market given its supply agreements. This would roughly equate to about $26 per boe (barrels of oil equivalent) for the dry gas. Whereas the liquids (light crude oil or condensate) could be priced (today) at $90 per barrel or higher.

A commercial discovery at Qana would kick off a years-long unitization negotiation, appraisal process, market development (for natural gas) and development. It could easily be seven to 10 years before Qana gas lands onshore Lebanon. The domestic market for discovered gas is small and the ability to pay for larger volumes of gas offtake is probably limited. Domestic gas market development in emerging economies is hard work and takes a long time. But has a higher probability of solving some of the energy problems of Lebanon.

A sufficiently large natural gas discovery of perhaps 12 to 15 Tcf could support an LNG export project and generate substantial returns to a Lebanese government but would not yield the macroeconomic benefits of a domestic gas development. An alternative option, requiring political and commercial relationships between Lebanon, Israel and Egypt, could see substantial volumes monetized via a submarine pipeline into a possible Leviathan Phase 2 tie-in to the offshore Egyptian gas infrastructure. While this seems almost unimaginable, so did an Israeli-Lebanon marine border and unitization agreement seem a short while ago.

There remains the potential for high liquids content in a commercial discovery at Qana. The value of a large liquids resource would be significant and could be monetized more quickly than a large natural gas discovery. In all of these options, a portion of the gas resource could be earmarked for a domestic market even if modest, initially. It would be ironic given that the allure of large, natural gas resources is what brought all of the Lebanese factions to the bargaining table, but it could be a large liquids resource which is actually served. But, an influx of cash flows directly into the coffers of the Lebanese government may damage even further the transparency that the Lebanese population demands of its government at this time.

The most likely scenario would see the provisionally accepted border agreement go into place in the coming weeks. Both the current Israeli and Lebanese governments see substantial benefits in the ratification of the provisionally accepted border agreement. This agreement would establish a marine border between the two countries, which among other aspects, establishes that the Energean-operated Karish (and North Karish) fields are 100% in Israel’s offshore. A second critical aspect places the appraisal and potential development of the Qana prospect within Lebanese government jurisdiction and provides for royalty payments to the Israeli government should commercial production be achieved. Karish field production would commence by or before the end of this year, barring operational issues. The North Karish field could also be producing in a few months. And it is likely that an exploration well on the Qana prospect would be drilled within the next two years.

Should there be a commercial discovery at Qana, a portion of the assumed reserves could fall within Israel’s offshore territory. This triggers the negotiated requirement that the two governments must work together to sort out the host of arrangements required to unitize any discovered resources, develop cross-border infrastructure (should that be required) and manage revenue sharing from fields. that straddle the border.

This scenario is not a fait accompli. Israel’s caretaker government may not be able to formally confirm its approval of the agreement. Hezbollah in Lebanon may attempt to disrupt the agreement, although current thinking is that they would not stand in the way of an agreement which is perceived to be a positive for the people of Lebanon. Moreover, the Qana prospect has substantial technical risks. Exploration wells could be dry holes or yield sub-commercial volumes of hydrocarbons. However, the experience of working with the Israelis and foreign companies may lead to the development of other prospects in Lebanon’s offshore which have potential, even though Qana may not yield satisfactory results.

Fundamentally, what do the two sides get from the agreement? The Israelis receive the ability to proceed with full exploitation of the natural resource base in their northernmost offshore, and more importantly, respite from a continuing cycle of meaningless violence on its northern border and a more stable neighbor. Lebanon gets the opportunity to test its best potential for a different and independent energy sector, and perhaps even a different economy if large natural gas resources are proven and can be developed.

A successful outcome will eventually require that working groups of Lebanese and Israelis must sit down, day in and day out to work out the technical and commercial complexities inherent in cross-border resource development. Perhaps the daily process of producing and then monitoring success will yield the longest lasting political dividend to both sides of the newly agreed marine border.

Gerald Kepes has more than 35 years of experience as a consultant and petroleum geologist in the global energy industry. Most recently, he was vice president in energy & natural resources for IHS Markit, and previously, a PFC energy partner, where he established PFC’s global upstream consulting practice. He also held various positions with a US oil company in North Africa and the Middle East.

We're glad you're interested in this memo.

Memos are one of several features available only to PRO Expert members. Become a member to read the full memos and get access to all exclusive PRO content.

Already a Member? Sign in

The Middle East's Best Newsletters

Join over 50,000 readers who access our journalists dedicated newsletters, covering the top political, security, business and tech issues across the region each week.

Delivered straight to your inbox.

Free

What's included:

Free newsletters available:

- The Takeaway & Week in Review

- Middle East Minute (AM)

- Daily Briefing (PM)

- Business & Tech Briefing

- Security Briefing

- Gulf Briefing

- Israel Briefing

- Palestine Briefing

- Turkey Briefing

- Iraq Briefing

Premium Membership

Join the Middle East's most notable experts for premium memos, trend reports, live video Q&A, and intimate in-person events, each detailing exclusive insights on business and geopolitical trends shaping the region.

$25.00 / month

billed annually

$31.00 / month

billed monthly

What's included:

Memos - premium analytical writing: actionable insights on markets and geopolitics.

Live Video Q&A - Hear from our top journalists and regional experts.

Special Events - Intimate in-person events with business & political VIPs.

Trend Reports - Deep dive analysis on market updates.

We also offer team plans. Please send an email to pro.support@al-monitor.com and we'll onboard your team.

Already a Member? Sign in