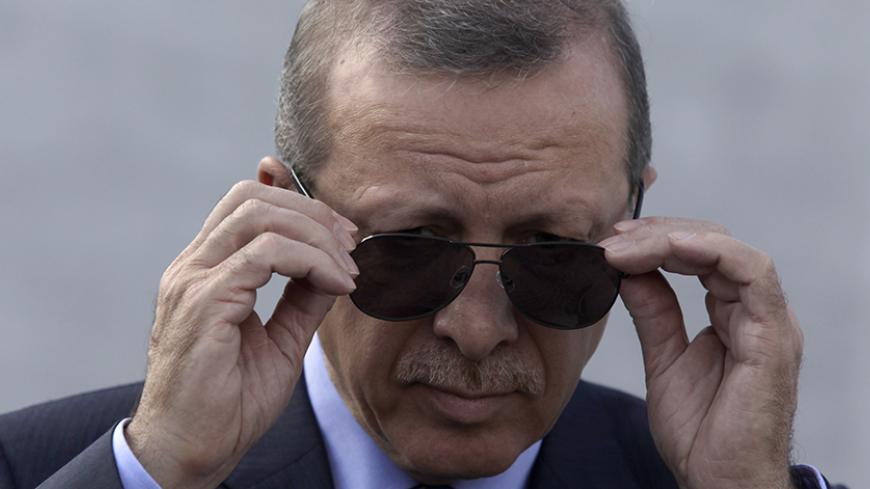

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is stepping up his rhetoric to convince his Justice and Development Party (AKP) voters that their leader is closer to God than they are.

During his term as prime minister, Erdogan used to make long speeches at weekly AKP parliamentary meetings, which most television channels broadcast live. After he ascended to the presidency, his audience of AKP lawmakers was replaced by mukhtars, elected leaders of villages and neighborhoods, of which there are 53,000 in Turkey. At certain intervals now, he invites several hundred selected mukhtars to the presidential palace for his speeches, again, broadcast live by almost all television channels.

In one of these speeches earlier this year, Erdogan defied his state of besiegement, the result of his own dead-end foreign policy, assuring the mukhtars that help would come from above. "This or that country may be against us, opposing us — none of this matters,” he said.

"What does the commandment say? Allah is sufficient for us, and he is the best disposer of affairs. Without this faith of ours, we could have never confronted the Byzantine army, the world’s greatest military power at the time, in the Battle of Manzikert with a force of 20,000 or 30,000 people. Without this faith of ours, we could have never established the most powerful state in history and kept it alive for 600 years.”

Erdogan seems to have developed an urgency to take his personality cult to new, more "celestial” heights, a drive that goes far beyond the "Allah is with us” rhetoric Erdogan deploys in the face of challenges.

Even a documentary that aired a month ago on the pro-government A Haber channel about the anniversary of the so-called Feb. 7 crisis of 2012 brought to light the brewing conflict between Erdogan and the Gulen movement. The tense episode saw Gulenist prosecutors make an unsuccessful attempt to arrest Hakan Fidan, Turkey’s intelligence chief, who was then Erdogan’s closest confidant in the echelons of the state. According to the documentary, a celestial intervention foiled the attempt.

Since then, statements and behaviors adding transcendent and holy dimensions to the Erdogan cult have become more and more frequent. Take, for instance, the stunning remarks AKP lawmaker Yasin Aktay made during a parliamentary debate last week. Erdogan is “one of the best things, one of the best people this country has seen,” Aktay said, adding, “We say ‘Salli Ala Muhammed’ when we see him.” He was reciting an Islamic phrase, known as “salavat,” used to salute and praise the Prophet Muhammad or to express allegiance to him.

In another recent incident, the head of an AKP youth branch in Istanbul posted on Twitter a picture of a water glass Erdogan had used, as if presenting a fetish object. “This is the glass from which our president drank water while making his speech,” he wrote.

In desperate situations, Turks say, “It’s now up to Allah.” One could say Erdogan’s foreign policy, too, is “now up to Allah.” It does seem Turkey will need a miracle to break free from the isolation induced by its foreign policy — unless the right players change the prevailing conditions.

With Russia, Turkey has been in a state of cold war, prone to hot confrontation, ever since it downed a Russian jet Nov. 24. With the United States and other Western allies, relations have plunged into a deep confidence crisis over Turkey’s shelling of Syrian Kurdish forces and its failure to provide expected support against the Islamic State.

As the external risks increase, strain is also building up on the domestic scene. Bent on controlling the government’s strings with no tolerance of any in-house criticism, Erdogan is causing the AKP to creak and possibly crack. His disagreements with Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu are said to be growing. A group of former AKP heavyweights led by ex-Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc has formed a dissident faction, enlisting support from former President Abdullah Gul.

In the predominantly Kurdish southeast, Erdogan's battle against the Kurdistan Workers Party — afoot since July — rages on in cities and towns with dramatic consequences remindful of the destruction and humanitarian disaster in Syria. As the death toll keeps rising on both sides, fears are rife that the conflict, affecting mostly urban areas at present, will escalate and expand in the spring. No prospect for an end to the bloodshed is currently in sight.

In this menacing atmosphere of stalemate, Erdogan has shown no sign of giving up his dream to install a system of executive presidency, which would confirm him constitutionally as the “one man.” To overcome internal and external obstacles and advance his goal, he is, as always, trying to generate support from his Sunni conservative base, which he sees as loyal backers and admirers.

While Erdogan’s supporters are busy exalting him, the major topics of his Islamic agenda have become more prominent in his speeches lately. On March 5, while addressing the members of an association fighting addictions and harmful habits, he spoke of how the “new Turkey” under his leadership was rejecting alcohol.

“The Jacobins of the one-party era [after modern Turkey’s creation in 1923] encouraged alcohol consumption in the name of Westernization and modernization," Erdogan said. "Alcohol was used as a tool to forcefully transform society, strip its identity from it and tear it apart from its values,” he said. “Today, as country and nation, we are in the process of building a new Turkey. Thankfully, that dark mentality has been largely disabled despite occasional resurrections.”

On Feb. 27, in a speech at the congress of a religious foundation, Erdogan underscored the importance of imam-hatip schools, which provide Quranic education, stressing, “Our target is a devout generation.”

So while doing politics in the “holy realm,” does Turkey’s Islamist president truly believe he has a divine mission? What he believes, in fact, is not very important at present. The critical question is whether his supporters believe it.