In a Dec. 11 interview about his new novel, Nobel laureate Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk commented on the ongoing reverberations of the large-scale corruption scandal that erupted in Turkey a year ago. “We have plenty of good reasons to oppose the incumbent government,” Pamuk told the Cumhuriyet daily. Asked to elaborate on those reasons, he said, “Let me tell you two of them. The first is freedom of thought and expression and the [government’s] repressive rule. The second is the things we became aware of after [the probe of] Dec. 17, that is, a disgraceful corruption. These two are reasons enough for a lifelong opposition to a government.”

Pamuk’s remarks show that the corruption cases and allegations against the government that emerged from the operations and probes of Dec. 17 and Dec. 25 last year have left scars in the popular conscience. Millions of dollars stashed in shoe boxes, bribes delivered to their recipients in chocolate packages, a gigantic gold smuggling scheme conducted through an Iranian “businessman,” the arrest of ministers’ sons, the resignation and dismissal of ministers and shameful corruption conversations wiretapped legally and illegally are some of the episodes of the probes now engraved in public memory.

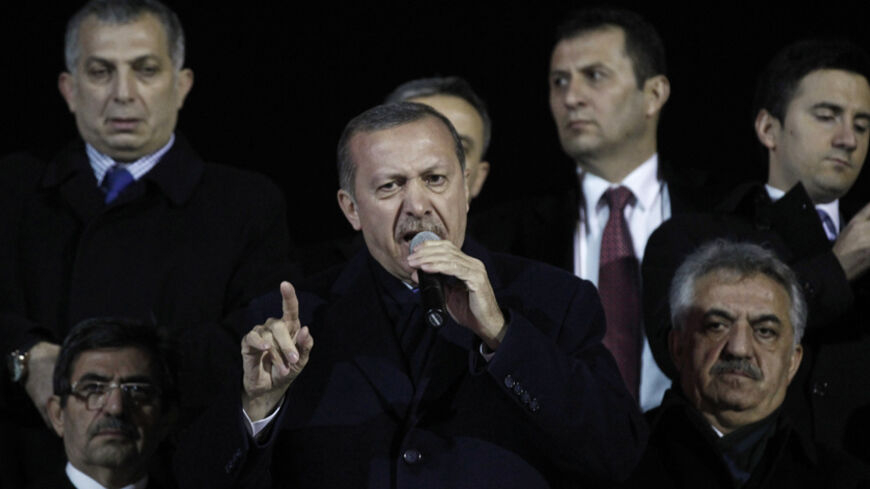

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, prime minister at the time, and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) government mounted an extraordinary effort to thwart and then cover up the probes at the expense of overstepping the law and eliminating judicial independence. They started by interfering in the judiciary to prevent planned detentions in the Dec. 25 probe, which targeted crony businessmen. The pro-government media, meanwhile, portrayed the probes as a coup attempt orchestrated by the Gulen community.

The de facto coalition between the AKP and the Gulen community devolved into an open war. The government removed from office thousands of police and judicial officials on the grounds they belonged to the “parallel state” — the name it gave to the Gulen community. Some police officers were jailed pending trial.

The government had the community included in National Security Council documents as a "national security threat" and dismantled alleged Gulenist networks in the state, especially in the police and the judiciary. The counteroffensive was not limited to public institutions. The government also launched campaigns to socially isolate the Gulenists and exerted pressure to force the financial collapse of Bank Asya, which is known to be close to the community.

The government’s latest onslaught targeted top managers of media close to the community. On Dec. 14, police carried out raids in 13 provinces and detained 31 people — among them Ekrem Dumanli, editor-in-chief of the Zaman daily, the Gulenist media’s flagship, and Hidayet Karaca, president of the community’s Samanyolu TV, as well as other media employees and police officers — on charges they set up, run or belonged to a terrorist organization and were involved in organized forgery and slander activities.

The operation was the most dramatic so far against the Gulen movement, not only because it targeted journalists and press freedom, but because the police raided Zaman’s head office in Istanbul to detain Dumanli.

The Gulen community has clearly taken a huge blow in its war with the “political Goliath.” Would its decision-makers have given the go-ahead for the Dec. 17 and Dec. 25 operations had they been able to foresee the dramatic state of affairs today? This question awaits a sincere answer.

2014 versus 2013

For Erdogan, 2013 was a real “annus horribilis” — first because of the Gezi Park resistance and then because of the corruption probes. Without his extraordinary performance, the disasters could have continued through 2014, especially at the ballot box.

The timing of the corruption probes was noteworthy — three months ahead of the March 30 municipal polls. The impact of the corruption scandal could have dealt the AKP a serious electoral blow and cause it to stumble. This was perhaps the intended outcome but it did not materialize. Drawing on his indisputable clout over AKP voters and media power, Erdogan managed to weather the elections with lesser losses than expected. Then, on Aug. 10, he became Turkey’s first popularly elected president, mustering 52% of the vote in the first round. Hence, the corruption probes failed to derail the plans Erdogan made for his political career.

Then, it was time to cover up the probes. On Sept. 3, a decision not to prosecute was issued for the 96 suspects in the Dec. 25 corruption and bribery investigation, which included Erdogan’s son Bilal. Heeding the AKP’s “coup” theory, the Istanbul chief prosecutor’s office said in its decision that “those who launched the investigation sought to forcefully unseat the government under the cover of a lawful investigation.”

A similar decision not to prosecute followed on Oct. 19 for the 53 suspects in the Dec. 17 leg of the probe, on grounds the investigation had been launched unlawfully and the alleged crimes had not materialized.

In a further move Nov. 26, an Ankara court imposed a media ban on the sessions of a parliamentary inquiry commission created to examine the charges against and question the four former AKP ministers who had either resigned or had been dismissed over the Dec. 17 probe — former Economy Minister Zafer Caglayan, former Interior Minister Muammer Guler, former EU Affairs Minister Egemen Bagis and former Environment and Urban Affairs Minister Erdogan Bayraktar.

But did the media ban and the closure of the files heal the scar the corruption probes inflicted on the government? An affirmative answer to this question is impossible.

The Erdogan government may have badly battered the Gulen community, but has failed to remove the “dagger” the community stabbed in its back on Dec. 17 and Dec. 25. And this dagger — in other words the public perception of corruption — continues to be a festering boil on the body of the “political Goliath.”

Had this corruption perception not existed, Erdogan’s pompous new palace of 1,150 rooms and an actual cost that well exceeds the stated $1 billion figure would not have been debated in the context of corruption among a large portion of the Turkish public. Similarly, neither Erdogan’s new, luxury airplane nor the 1 million lira ($424,000) official car of the head of the Religious Affairs Directorate would have attracted that much attention.

With general elections looming next year, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, Erdogan’s appointee as his successor, must be well aware of the realities, for he is making cautious and measured efforts to distance himself from the corruption scandals, in which he was never implicated in the first place, including frequent statements against corruption.

On Dec. 8, for instance, Davutoglu reminded journalists accompanying him on a flight back from Athens of the remarks he made in a speech after his election as AKP chairman in August, following Erdogan’s ascent to the presidency: “I’ll break off the arms of anyone who gets involved in corruption, even if it is my brother.” Earlier, at a press conference at the end of the G-20 summit in Australia on Nov. 16, at which Turkey took over the group’s presidency, Davutoglu pledged that Turkey would “intensify the struggle against corruption during its presidency and draw up a strategy on the issue.”

Meanwhile, one has to acknowledge that the media ban has been of little use. On Dec. 9, for instance, the mainstream mass circulation Hurriyet appeared with a front-page headline asking, “Where does this money come from?” The story was about a question posed to Caglayan at the parliamentary inquiry commission concerning a suspicious transfer of 2.5 million Turkish lira ($1.06 million) to his bank account. The most noteworthy detail in the story was that the question to the AKP’s former economy minister was posed by another AKP member, commission Chairman Hakki Koylu.

Similarly, Etyen Mahcupyan, the ethnic Armenian intellectual appointed recently as Davutoglu’s chief adviser, keeps emphasizing in interviews and writings the harm the AKP incurs from the corruption scandals. The fact that Mahcupyan retains his post despite his critical tone suggests that his warnings have Davutoglu’s approval. Most recently, Mahcupyan told Hurriyet in a Dec. 15 interview, “Trying to cover up the corruption files forever could eventually result in a hefty price for the AKP.”

Obviously, Davutoglu wants to draw a line between his term as prime minister and the corruption scandals. At the same time, he wants to battle the Gulenists, whom he denounces as coup plotters over the corruption operations. Pulling off those two tasks simultaneously is not easy at all.