Ankara has broken its official silence and provided details on ongoing reconciliation talks with its historic foe, Armenia. In a lengthy background briefing, a senior Turkish diplomat described the substance of the talks, what their goal was and the multiple challenges that lie ahead. Speaking on the sidelines of the annual ambassadors’ huddle organized by the Turkish Foreign Ministry, the official stressed that in order to avert “big disappointments,” the sides were focused on confidence-building steps to be taken “one at a time.” The official was addressing critics’ claims that Turkey is deliberately keeping the pace of the talks slow in order to allow its regional ally Azerbaijan to pressure Armenia into further concessions on the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Turkey played a key role in helping Azerbaijan wrest back huge chunks of territory from Armenia in a brief and bloody war in the fall of 2020.

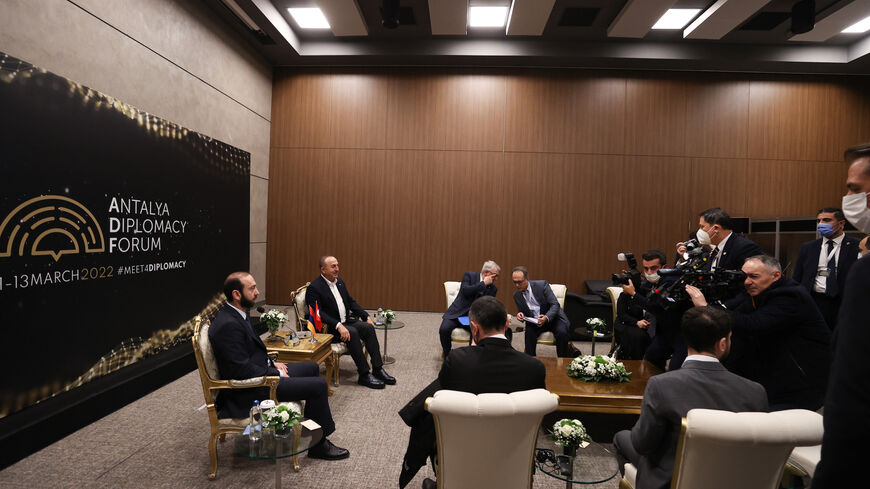

The official said that Serdar Kilic, Turkey’s special envoy for normalization with Armenia, was ready to travel to Yerevan for the fifth round of talks and insisted that these be held either in Turkey or Armenia. The previous rounds were held initially in Moscow, then in Vienna. Armenia is reluctant to accede to the Turkish demand until the land border between the two sides is fully opened.

Turkey was the first country to recognize Armenia when it declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1992. But diplomatic relations were never established as Armenia and Azerbaijan slid into conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh.

The official acknowledged that the current picture was far from what was desired and that both sides needed to try harder. The first concrete measures agreed upon so far since the sides began meeting in January were to commence commercial cargo flights between the two countries and open their long-sealed land border to third-country nationals.

The Turkish official said that launching the cargo flights involved “a host” of technical steps and details. The next step would therefore be for the sides to do their respective “homework” and meet in September to hash out a strategy. The aim is to commence the flights as soon as possible, the official said.

As for opening the land border, the official said that a delegation from the Turkish Foreign Ministry had toured the area and it was clear that the current infrastructure would not support travel between the two sides. It was unclear whether the bridge in the border province of Igdir that was built in 1940 was robust enough to carry buses. The official also mentioned the historic bridge that is among the ruins of the Armenian kingdom of Ani on the Turkish side. All that remains of the stone bridge that connects the two sides over the Akhurian river are two stubs. Work to restore the bridge would take a long time, the official noted. Repairing the bridge that was destroyed by the Russians would constitute “a very strong confidence-building step,” the official added.

The official noted that expectations among the people “were very high,” and that following the decision to open the land border to third-party nationals, those on the Armenian side had started converting their homes into restaurants and boutique hotels. “We must not dash their expectations,” he said.

The official said that trade between the two countries was currently conducted via Georgia. The volume of trade between Armenia and Turkey stands at around $230 million per year. Some 15,000 trucks are used for the trade. Should direct trade commence, this would benefit Armenia far more than it would Turkey. Bearing this fact in mind, said the official, Armenia “needs to be more constructive" and turn the situation into a “win-win for all.” He did not elaborate.

However, he was clearly referring to concessions on Nagorno-Karabakh and the so-called Zangezur corridor that would give Azerbaijan direct access to Nakhichevan, the tiny Azerbaijani exclave on the Turkish border. Viewed from Yerevan and particularly through the eyes of the Armenian opposition, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has been more than accommodating; he is capitulating, they would say, in ongoing talks with Azerbaijan. Pashinyan is sticking with the process as he views it as the best guarantee for economic prosperity and against a renewed war that would leave Armenia in an even frailer state.

In a recent interview with Turkey state-run Anadolu news agency, Azerbaijan’s foreign minister, Jeyhun Bayramov, said the corridor would be established whether “Armenia wants it or not.”

Azerbaijan is also demanding that Armenia relinquish all claims over Nagorno-Karabakh. Violence between the sides has flared up again along the lines of contact in the majority Armenian enclave, leaving three people dead.

The official kept the tone upbeat, noting that the fact that Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had spoken to Pashinyan over the telephone for the first time last month was “important in and of itself.” But the underlying message of the briefing was clear: The onus is on Armenia to expedite peace.