After handicrafts and TV melodramas a new and unlikely item has been added to Turkey’s list of cultural exports: psychedelic rock.

Legendary Turkish rock acts from the 1960s and 1970s — such as Mogollar, Baris Manco, Cem Karaca and 3 Hurel — now have a following in North America and Western Europe. Glossy reissues of Turkish rock LPs can be found in record stores from Chicago to Stockholm. American rappers Mos Def and Dr Dre have used samples of blistering guitar solos from Turkish protest-rocker Selda Bagcan in their songs. Bagcan herself, now 70 years old, plays packed festivals in Spain and the Netherlands with an international group of youngsters as her backup band. American actor Elijah Wood of "The Lord of the Rings" and musician Annie Clark have both come out publicly as fans of ‘60s Turkish rock.

This unexpected revival is not only happening abroad. Young people in Turkey have also been rediscovering these sonic experiments from the mid-20th century.

Anadolu Rock, as this psychedelic/progressive rock music from Turkey is called, is named after the Anatolian land-mass on which most of modern-day Turkey is situated. The genre boldly combined folk music traditions from the countryside with international rock music, with particular influence from bands like The Animals, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Traffic, Cream and Jethro Tull.

By listening to Anadolu Rock, Turkish youths have been reconnecting with a part of their country’s cultural history that many of them knew little about. Several young trendsetters have dedicated themselves to spreading the word.

“We didn’t know about the Turkish rock of the ‘60s and ‘70s when we were growing up,” publicist Gokhan Yucel told Al-Monitor. A military coup in 1980 cut off new generations from this earlier experimentalism. Attending high school in the mid-1990s, Yucel is part of a generation shaped by the amnesia of the post-coup period. Having chanced upon this forgotten music a few years ago, Yucel has made it his personal mission to make sure people in Turkey are aware of this musical history.

In 2014, Yucel collaborated with friends to create the Anatolian Rock Revival Project. This multi-platform project is most active on YouTube where the group posts little-known tracks from the ‘60s and ‘70s. Many of these songs only exist on 45 rpm records. Yucel and his collaborators not only rescue these songs from obscurity, they have them remastered for quality, adding English and Turkish subtitles.

Most significantly, the Anatolian Rock Revival Project commission illustrators to create lush, original cover art for each song. “These art pieces are like the sugar-coated pill to get people interested in learning more,” Yucel joked.

With more than 143,000 followers to date and effusive comments from viewers in Turkey and across the world, the Anatolian Rock Revival Project has inspired many to dig into the history of this unique musical synthesis.

Anadolu Rock got its start in the early-1960s. In 1964, chic young jazz singer Tulay German electrified listeners by performing the Turkish folk song “Burcak Tarlasi,” named after a field of the ancient Anatolian crop called bitter vetch.

The anonymous folk song is written from the perspective of a peasant woman harvesting grain in the fields and railing against the feudal lord. German and her collaborator Erdem Buri took this song, adapted the instrumentation and out came a swinging version of “Burcak Tarlasi” complete with piano, electric guitar and horns.

The smartly dressed audiences in Istanbul and Ankara’s elegant nightclubs couldn’t get enough of this song. A new musical genre was born.

Prior to “Burcak Tarlasi,” Turkish pop music was dominated by note-for-note copies of songs popular abroad. Quick to realize that the Turkish public was hungry for something more innovative, Hurriyet newspaper set up a contest called the Golden Microphone in 1965. Competitors were asked to use the melody and lyrics of Turkish traditional songs and perform them with Western instruments. Between 1965 and 1968, many of the major names of Turkish rock music were launched by Golden Microphone, including Siluetler, Mavi Isiklar, Fikret Kizilok and Erkin Koray.

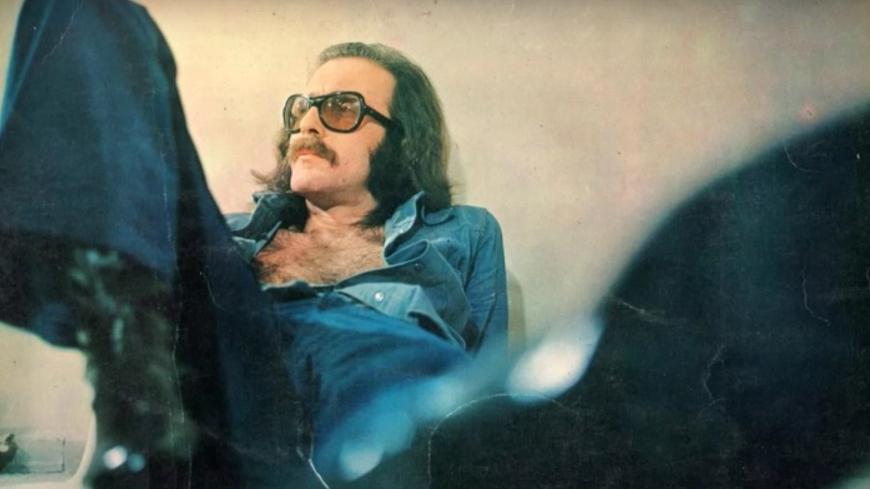

It would take until 1970 for this genre to receive a name. Giving an interview with the press after a concert tour through the Anatolian countryside, the long-haired and leather-dressed members of Mogollar dubbed their music “Anadolu Pop.” The genre later came to be known as “Anadolu Rock” and “Anadolu Psych.”

In the first half of the 1970s, Anadolu Rock swelled in popularity. Turkish rock bands cut their teeth adapting local folk. Now they started going in more original directions. Feeding off the energies of the ascendant student movements, artists like Cem Karaca and Selda Bagcan penned revolutionary anthems. Erkin Koray combined trippy progressive rock with folk instruments like the zurna, a reed instrument known for its shrill, infectious cry. Baris Manco, famous for his handlebar mustache and eccentric clothing, composed futuristic rock operas.

Anadolu Rock maintained its prominence into the late 1970s. However, the military coup of 1980 brought the genre, already struggling to keep up with the move from vinyl to cassette, to an end. Left-wing rockers faced repression while the gloomy political atmosphere increased the popularity of the melancholy Arabesque genre.

Despite being banned on the radio and facing arrest by the military rulers, Edip Akbayram is one Anadolu Rock musician who was able to re-enter the limelight once the shadow of the coup had passed. When asked why he thought his recordings from the 1970s are suddenly in vogue, he stressed the differences between being a recording artist then and now. What sounds retro and exciting to many young fans actually comes out of a different standard of musicianship.

He told Al-Monitor, “Young people know that much of today’s music is empty. Back then recording technology in Turkey was limited; sometimes there was only a single microphone. The studios had one or two tracks maximum, so we had to be able to play everything perfectly from start to finish.”

Akbayram said that he finds satisfaction in going online and seeing that a record he made in the 1970s can fetch a hefty sum in Europe or the United States.

For Reha Oztunali, the founder of Tantana Records, based in Istanbul, also confirmed to Al-Monitor that Anadolu Rock has been experiencing a resurgence of interest. He lists two main reasons - the vinyl revival and digital video platforms. Since roughly 2007, vinyl records have become popular among music fans. Intrepid record companies like Finders Keepers have printed reissues of psychedelic rock from Turkey and all over the world.

This hunger for vinyl, combined with the massive amount of rare music uploaded onto YouTube, means that obscure tracks once only known to the most dogged of collectors are now just a click away.

Kornelia Binicewicz, a Polish DJ and record collector based in Istanbul, is a living example of this passion for vinyl. She has also witnessed firsthand how excited European audiences are for Turkish music from the '60s and '70s. “At first it was actually audiences in Turkey that were more skeptical,” she told Al-Monitor. “‘Fusun Onal,’ they would say to me, ‘what could possibly be interesting about the recordings of an old singer like her!’”

But the intense interest abroad has pushed businesses within Turkey to re-evaluate this legacy. Binicewicz has paired up with Uzelli Records and Sony Music Turkey to curate compilation albums using forgotten tracks from their archives. The latest of these compilation LPs is "Turkish Ladies: Female Music from Turkey 1974-1988."

Yucel, whose Anatolian Rock Revival Project has perhaps been most instrumental in raising awareness, sees this music as more than a passing phase or marketing venture. He thinks that Anadolu Rock can play a crucial role in changing people’s perceptions, both in Turkey and abroad.

At a time when scores of creative, young people are fleeing Turkey in droves, the Anatolian Rock Revival Project is attempting to inspire those who remain to be bold and attempt new things.