“He hit me four times from behind. … I fell on the floor,” says a muffled voice off-screen. Then the camera pans in on a bed-ridden woman as she drags out the reply to the question of who hit her. “Neptun … my husband.”

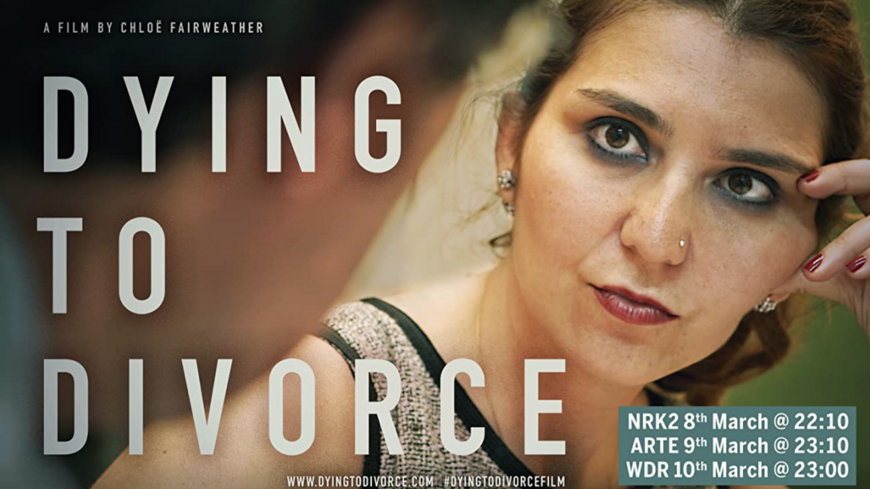

Kubra, a former TV anchor who lost her mobility and speech after a brain hemorrhage, is one of the heroines of “Dying to Divorce,” an 80-minute documentary on gender violence and femicide in Turkey. Directed by Chloe Fairweather and produced by the Turco-British team of Sinead Kirwan, Ozge Sebzeci and Seda Gokce, the film is Britain’s official entry in the Academy Awards for best international feature film. The shortlist is expected to be announced on Dec. 21.

The documentary took five years to make and at times felt impossible to finish, according to Fairweather. It tells the story of Kubra, an up-and-coming journalist referred to by her first name in the film, and Arzu, a traditional homemaker who was married off at 14 to a man 11 years her senior. Both of their cases made headlines in Turkey due to the perpetrators’ repetitive and brutal attacks and the reduced sentence of one year and 15 days given to Neptun Eker in 2018.

Arzu Boztas, mother of six, left her abusive husband in 2016 when she learned that he had raped a mentally disabled, underaged neighbor. In order to punish her for walking out, her husband shot her in her arms and legs, sentencing her to a wheelchair for the rest of her life. As he turned the rifle on her, Arzu begged him not to fire at her arms so that she could take care of her kids. Unmoved, he stepped on her hand and pulled the trigger, aiming at her elbows. He was sentenced to 35 years — 20 years for attempted premeditated murder and 15 years for rape of an underage girl. Arzu has gone through 16 operations but hasn't recovered the use of her arms. “Her situation is getting worse, not better,” Sebzeci, one of the producers, told Al-Monitor.

Fairweather's debut feature narrates not only their story but the legal battle they have faced with the help of Ipek Bozkurt, an activist and lawyer who has worked for Turkey’s We Will Stop Femicides Platform, and We Will Stop Femicides Platform member Aysen Ece Kavas.

“We chose these two women because they are fighters,” Bozkurt told Al-Monitor on the phone from Scotland, where she is attending the premiere of the film. Its UK debut in cinemas coincides with “16 Days of Activism,” the United Nations campaign against gender violence.

“This is not some drama that expects the audience to weep. When I see women like Arzu and Kubra, I simply put on my gloves and I do not give up,” she added.

The feisty lawyer, with deeply shadowed eyes and a diamond stud on her nose, has a knack for strong, deadpan statements. In the film, she looks squarely at the camera as she says, matter-of-factly, “This country protects murderers who want to punish their wives, their girlfriends and daughters who want to have different things.” Then she talks about the tattered justice system. “When people are afraid of their own lives, their children’s lives, it is impossible to have justice.”

At the beginning and end of the documentary, the online Digital Memorial, which the platform updates daily in commemoration of femicide victims in the country, ticks off like a sinister taximeter, attesting to the fact that there are many out there who, unlike Arzu and Kubra, lost their lives because they asked for a divorce, walked out or simply failed to reply to their husband’s phone call.

Even for those with activists or lawyers to fight in their corner, the judicial process is long, taxing and feels rigged against them. “The Turkish courts are overloaded, so justice is slow, and it is rare to see the men — the perpetrators of violence — get the full sentence they deserve,” Bozkurt said. “But worse, the courts see those murders as individual cases rather than a collective, political crime. That is why you need to have a holistic approach that focuses on punishment, prevention, policy-making and monitoring. That is why we need the Istanbul Convention.”

In an overnight decision on March 10, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that Turkey would withdraw from the landmark Council of Europe convention, the far-reaching accord that holds states responsible for protecting women from gender-based abuse and violence, persecuting abusers and promoting policies to prevent harassment. Main opposition parties have pledged to get back into the convention as one of their first acts if they win the elections, and women’s groups say that the withdrawal has encouraged violence against women. There have been more than 160 cases of femicide and 138 suspicious deaths of women since March 20 — when Turkey announced it was leaving the Istanbul Convention — until the end of November, according to the femicide platform.

“The documentary offers a women’s gaze to femicides. … And it is the UK’s entry to the Oscars — well, we did not expect that!” said Sebzeci, a photojournalist who has covered gender issues for a decade.

“It deserves to win,” Bozkurt told Al-Monitor. “‘Dying to Divorce’ addresses a global issue through the situation in Turkey — it is not only here that women face harassment and gender-based violence. Femicides are everywhere.”

This is not the first time that the story of Turkish women has made it to the Oscars. In 2015, France nominated “Mustang” — a Turkish-language drama co-written and directed by Deniz Gamze Erguveni — for the Academy Awards' best foreign language film. A co-production of France, Germany and Turkey, the film told the story of five orphaned sisters as they fought against incest and forced marriages in a conservative society.

“Particularly after Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, the Turkish women’s movement became more united and more vocal,” Sebzeci said. “It has become a strong symbol for women’s movements everywhere.”

According to a report by Plan International titled The Protection of Young Women and Girls in the Middle East and Northern Africa, MENA ranks lowest on the Global Gender Index, scoring minimally on fundamental indicators such as health, education, and economic and political participation. Gender-based violence is the most common violation of rights, with one in three women in MENA having experienced or being at risk of experiencing physical or sexual abuse in their lifetime. The ratio is also 3:1 in Turkey.

“Dying to Divorce” will be shown in Istanbul and Izmir during the Human Rights Film Festival in December. Earlier this year, the producers asked the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts to screen it during its film festival but were refused on the grounds that the film was “too politically explosive,” Bozkurt said.