SYUNIK, Armenia — A small hotel in Goris, a sleepy tourist resort in the Syunik region in southern Armenia, seems an unlikely backdrop for geopolitical maneuvers between Western powers, Turkey, Russia and Iran. But that is what the Hotel Mirhav, a trio of rustic cottages filled with antique kilims and copperware, has become amid fears of renewed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan from which Iran could emerge the biggest loser.

Numerous families have been sheltering here since Dec. 12, when Azerbaijan effectively cut off access to their native Nagorno-Karabakh, letting a group of self-described Azerbaijani “eco-activists” with no history of environmental advocacy barge through Russian peacekeepers to block the sole road linking the disputed enclave to Armenia.

The Armenian-majority region lies within Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized borders but has governed itself under the name of the Republic of Artsakh since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

As regional powers butt heads, a full-blown humanitarian crisis is unfolding, with baby formula, medicines and other vital supplies growing scarcer by the day. Schools have been shuttered and Nagorno-Karabakh’s 120,000 inhabitants put on ration cards as Azerbaijan continues to disrupt gas and electricity supplies amid sub-zero temperatures. Armenia’s leaders accuse Azerbaijan of seeking to ethnically cleanse Nagorno-Karabakh by starving the local population and forcing it to leave.

Azerbaijan’s strongman President Ilham Aliyev hinted as much in a Jan. 10 TV interview, saying, “Conditions will be created for those who want to live [in Nagorno-Karabakh] under the flag of Azerbaijan. Like the citizens of Azerbaijan, their rights and security will be ensured.

“For whoever does not want to become our citizen, the road is not closed, but open. They can leave. They can go on their own, or they can ride with [Russian] peacekeepers, or they can go by bus. The road [to Armenia] is open.”

Rebukes from the European Union and stiffer ones from the United States have had little impact so far as the siege entered its 51st day today. The International Crisis Group ranked Nagorno-Karabakh second after Ukraine among the top 10 conflicts to watch in 2023, warning in a report this week that “another war on Europe’s Eastern flank is real.”

“I am stuck here with my two children. It’s an intolerable situation and I have no idea when it will end,” said Inna Gasparyan, whose husband and two other children are marooned in the capital Stepanakert. “The kids need vegetables. The shops are empty. What more can I tell you?” she said, her voice trailing off in despair.

At a nearby table in the Mirhav’s dining room, a clutch of men and women confer in hushed tones, studiously avoiding eye contact with fellow guests. They are members of the European Union’s 40-member civilian observer mission that is headquartered at the Mirhav. They were deployed to monitor a 250-kilometer (155-mile) cease-fire line after Azerbaijani troops crossed the border on Sept. 12 and captured a set of strategic heights inside Armenia. By the time Russia brokered a cease-fire two days later (Armenia's parliament speaker credited the United States), as many as 300 servicemen were killed on both sides, marking the gravest escalation since Armenia and Azerbaijan went to war for a second time over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020.

3263.jpg)

The EU observer mission at the Mirhav hotel in Goris, Armenia, Jan. 19, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

With Turkey and Israel’s backing, Azerbaijan emerged victorious, snapping back all of its land occupied by Armenia in a previous conflict that erupted as the USSR disintegrated and shortening Iran’s de facto border with Armenia. It also took around a third of Nagorno-Karabakh. It is now thought to control roughly 200 square kilometers (124 square miles) of Armenian territory. For a newly muscular Baku, that wasn’t enough.

Catastrophe for Iran

The deeper worry is that seizing on Russia’s Ukraine woes and Iran’s domestic unrest, Aliyev will go for a bigger prize: a land and rail corridor that would link Azerbaijan via Armenia’s southernmost province Syunik to its largest exclave Nakhichevan and on to Turkey. It would separate Iran from Armenia, its sole Christian neighbor and a vital stepping stone to Western markets. Armenia, in turn, would be effectively deprived of potential military support from its friendliest neighbor, Iran.

The Zangezour corridor “would be a geopolitical catastrophe for Iran,” said Hamidreza Azizi, an Iranian visiting fellow at the Berlin-based think tank SWP.

Vahan Kostanyan, Armenia's deputy foreign minister, told Al-Monitor in an exclusive interview, “Azerbaijan has three objectives: the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh, to provoke large-scale military tension in the region and finally to push the Armenian side to give an extra-territorial corridor.” Kostanyan added, “Iran is an important partner. The border with Iran is of utmost importance to us. We have two closed borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan, thus Iran and Georgia are our only gates to the outside world.”

Azerbaijan has angrily dismissed Armenia’s pleas for international action as propaganda, saying that the Red Cross and Russian peacekeepers are assuring the flow of food and medicine into Nagorno-Karabakh.

On Jan. 23, the EU announced that it was establishing what it called a Common Security and Defense Policy mission in Armenia. As many as 100 civilian observers are to be deployed to ensure that cease-fire lines are holding along the Azerbaijani border. As Schahen Zaytounchian, a retired Iranian-Armenian neurosurgeon who runs the Mirhav hotel, opined, “The presence of observers gives me a little bit of security. Only an idiot can make some aggression.”

But their mandate does not extend to Nagorno-Karabakh, for which it would need Azerbaijan’s consent. That is unlikely to be forthcoming. Russia’s Foreign Ministry lambasted the EU move as a combined effort with the United States “to gain a foothold at all costs.” Critics say the EU is seeking to make amends for a gas deal it signed in July with Azerbaijan to double gas imports in order to make up for the loss of Russian gas as a result of Ukraine-linked sanctions. The deal will have only further emboldened Baku.

Old railway station in Meghri, Armenia, on the Iranian border that used to serve Soviet-era lines in the South Caucasus, Jan. 20, 2023. (Stepan Adamyan)

Iran has always balked at the injection of more foreign actors in its backyard. However, Azizi contended, “The Europeans being there could balance Azerbaijan and that’s in line with Iran’s interests,” even though relations between the Islamic Republic and the EU are at an all-time low.

Aliyev has made no secret of his designs on the so-called “Zangezour corridor,” calling it a “historical necessity” and asserting repeatedly that it will “definitely be opened whether Armenia wants it or not.” Iran has called any attempt to alter its borders a "red line."

Tensions between the Shia-majority neighbors are escalating beyond Armenia. On Jan. 27, a gunman burst into the Azerbaijani Embassy in Tehran, killing the head of security at the mission and wounding two guards.

“We demand that this terrorist act be investigated and the terrorists be punished,” Aliyev said in a statement. Iranian authorities said the assailant, an Iranian man, had no political motives and that it was a “family affair.” But Azerbaijan isn’t buying it. Baku said it was shutting down its mission and withdrawing all its diplomatic staff from Tehran pending the results of thorough investigations. (The Azerbaijani consulate in Tabriz will continue to function.) Video footage of the attack showing an Iranian security guard sitting inert as the perpetrator armed with a rifle entered the embassy has inflamed public sentiments in Azerbaijan.

An Israeli listening post

Some Azerbaijani officials believe that Iran staged the assault to punish Baku for sending its first ambassador to Israel this month after three decades of ties. Until now, Baku has held back so as to maintain the support of Arab countries over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, explained Zaur Shiriyev, a South Caucasus analyst for the International Crisis Group. Yet ties between Azerbaijan and the Jewish state have been flourishing for long years.

Benyamin Poghosyan, a Yerevan-based pundit said, “Azerbaijan is becoming an Israeli outpost in the region. There are Israeli advisers permanently based in Baku,” he told Al-Monitor.

The presence of Israeli military officials is frequently rumored yet impossible to prove. It’s common knowledge, however, that Azerbaijan, which is among Israel’s top suppliers of oil, has acquired large amounts of weapons from the Jewish state. Open-source intelligence showed cargo planes ferrying them throughout the 2020 war. Nor is it a secret that Israel has long used Azerbaijan to spy on Iran.

In a bid to draw Baku to its side, Iran supported Azerbaijan, at least rhetorically, at the start of the 2020 war, not reckoning just how far Russia would allow it to advance. In a similar miscalculation, Armenia decided in 2020 to open its first diplomatic mission in Tel Aviv only for Israel to go all in with Azerbaijan.

Today, Azerbaijani security forces raided several media organizations in Baku accused of being on Tehran’s payroll. Seven people described as being part of an “Iranian spy network” were detained.

The newly inaugurated Iranian consulate in Kapan, Armenia, Jan. 28, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Since 2021, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps has conducted large-scale military drills, most recently in October along its frontier with Azerbaijan. The latest, “Mighty Iran,” included setting up pontoon bridges and crossing the Aras River, which separates the two countries.

Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian told the state-run IRNA news agency in an Oct. 19 interview, “Iran will not permit the blockage of its connection route with Armenia, and in order to secure that objective the Islamic Republic of Iran also launched a war game in that region."

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei warned in an Oct. 3 tweet, “Those who dig a hole for their brothers will be the first to fall into it.”

On Jan. 20, Iran’s ambassador to Armenia paid a visit to his country’s newly established mission in Syunik’s administrative capital, Kapan. “Armenia’s security is Iran’s security,” Abbas Badakhshan Zohouri told the Kapan news corps. A giant Iranian flag hoisted above the drab consulate is meant to telegraph Iranian heft to Azerbaijani forces lurking in the nearby mountains.

Iran’s hawkishness is music to Armenian ears. Kostanyan, the deputy foreign minister, told Al-Monitor, “We had intelligence that larger attacks were being prepared by Azerbaijan when it attacked Armenia last September. Iranian actions and statements helped to stop a further deterioration of that situation.” Others credit the United States for deterring Baku.

In the small town of Meghri on the Iranian border, restauranteur Asya Sarkisyan said business has remained thin since the 2020 war. With the threat of war growing, Sarkisyan said, “I don’t want to leave but I need to think about my children," adding, “Here in Meghri our hope is in Iran. But they will act in their own interest, of course.”

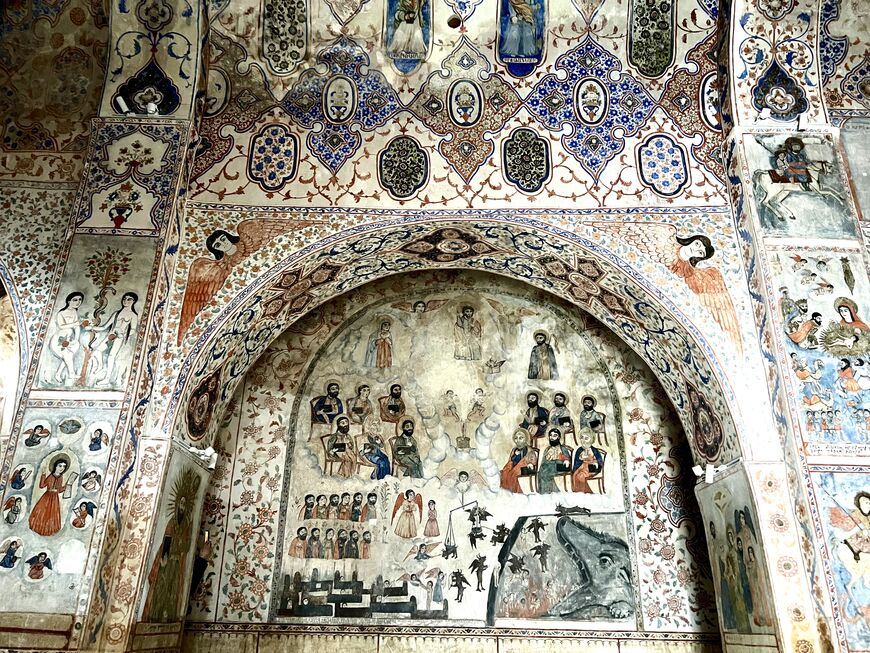

Syunik has strong cultural and historical links to Iran dating back to the early 16th century, when much of present-day Armenia was under Persian rule. The traces are seen in the wall paintings rendered in exquisite Persian miniature style in the 17th-century St Hovhannes church in Meghri.

Vardan Voskanyan, who runs the Iran department at Yerevan State University’s Faculty of Oriental Studies, told Al-Monitor, “We took a lot of things from Iran. Armenia is a museum of ancient medieval Iran.”

“Iran is the only country that supported us economically when Turkey sealed the border,” Voskanyan recalled. “You can’t trust the West. They will only help Armenia when it becomes another Ukraine for Russia. They will help us only if Armenia becomes anti-Iran.”

Persian influence is palpable in the 17th Century Surp Hovhannes Church in the Armenian town of Meghri on the Iranian border Jan. 20, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

In November, Armenia and Iran inked an accord to double the amount of natural gas that Iran sells to its neighbor in exchange for the latter’s electricity during a visit by Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to Tehran.

Two-way trade shot up by 43% last year and Yerevan remains a popular watering hole for Iranians in search of booze and carnal pleasures. On a recent night, a bouncer at the Manoto club, a basement dive in central Yerevan, expressed surprise when this reporter and an Armenian colleague sought entry, saying, “It’s all Persians in there, brother.” Sure enough, wisps of Farsi wafted above the din of disco music as bearded men of all ages gawked at exotic dancers writhing under the venue’s purple strobe lights.

Lonely democrat

Pashinyan, who led his country’s Velvet Revolution in 2018, ending decades of corrupt and repressive rule, has to tread carefully. He needs Western support, particularly that of Washington, as in the words of a senior Armenian official speaking not for attribution, “The United States is more interested in safeguarding a democratic Armenia than the EU.”

In September, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi led a delegation to Yerevan just days after the Azerbaijani incursion.

But Pashinyan is also in desperate need to rebuild his battered army. Russia is nominally Armenia’s top supplier, but it has reportedly yet to deliver hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of arms said to have been paid for by Yerevan, probably because they are being diverted to Ukraine. India is the only other country selling Armenia weapons, mainly because its arch-enemy, Pakistan is a staunch backer of Azerbaijan. Iran would be a natural source for military kit. Yet the slightest hint of such deliveries from Tehran could trigger Western sanctions at a time when this country of 3 million is more vulnerable than it’s ever been since declaring its independence from Moscow in 1991.

Acquiring Iranian weapons “is not on our agenda,” Kostanyan, the deputy foreign minister, told Al-Monitor.

Azerbaijan, meanwhile, is showing no such restraint. Mimicking Iran, it’s held several military exercises in the border region, most recently in December — a joint maneuver with Turkey called “Fraternal Fist.”

Ankara drones and military advisers helped cinch Baku’s 2020 victory and it's an advocate of a “Zangezour corridor” that would extend all the way to China. This would scrap its current dependence on Iran to reach Central Asian markets.

A cease-fire agreement brokered by Russia on Nov. 9, 2020, for Nagorno-Karabakh says that “all economic and transport connections in the region shall be unblocked.” Under its vaguely worded terms, Armenia is supposed to guarantee unobstructed passage through them and Russian border guards will oversee it all. However, Baku wants to be able to use the proposed artery through Syunik without being subjected to any Armenian customs controls. Armenia squarely rejects the idea, saying this would be a breach of its sovereignty. What if Azerbaijan, presumably with Turkish backing, were to up the ante and swallow a chunk of Syunik in order to attach Nakhichevan to its mainland?

The question weighs heavily in Akner, a village just northwest of Goris that was struck by Azerbaijani rockets on Sept. 13 during last year’s “two-day war.” One blew through the roof of the house shared by furniture salesman Edgar Salbuntz, his wife Ramela and his parents, Arevik and Kim. “Thanks to God we were at the neighbor's when it landed, otherwise we would all be dead,” Salbuntz told Al-Monitor as he pulled out what he said was a fragment of a Russian-made Grad rocket from a chest of drawers.

Like many in this mountainous region dotted with ancient monasteries and copper mines, he calls Syunik Armenia’s “backbone.” “If it’s gone, there will be no Armenia,” Salbuntz asserted. "But who can stand in Azerbaijan’s way?” he mused. On paper, it's Russia and her peacekeepers.

A piece of shrapnel from a rocket fired at his home near Goris, Armenia, by Azerbaijani forces on Sept. 13, 2022. Image Jan. 19, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

Armenia is a member of the Kremlin-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CTSO), comprising six former Soviet states. When one is attacked the rest are meant to ride to its defense. Misgivings about Russian support began to emerge when Moscow sat on its hands as Armenian forces were decimated in the early days of the 2020 war. The feelings grew when Moscow failed to intervene against Azerbaijan in the September flareup.

Olesya Vartanyan, the International Crisis Group’s senior South Caucasus analyst, told Al-Monitor, “Since the Ukraine war, we are seeing an even more assertive Azerbaijan. Russian containment and deterrence has all but disappeared.”

No Turkish delights

Turkey stepped into the vacuum on Azerbaijan’s side even as it sought to normalize relations with Yerevan. For Pashinyan, peace with Turkey was meant to fend off further attacks by Azerbaijan. So far he’s got neither.

After four rounds of face-to-face talks, diplomatic relations have yet to be established though there are hopes on the Armenian side that Turkey will allow its foreign minister to travel overland to a diplomacy forum planned for March in the Turkish seaside resort of Antalya.

Land borders between the two countries remain closed save for nationals of other countries, a first baby step decided last year. A second was to start cargo flights. Richard Giragosian, founding director of the Regional Studies Center, an independent think tank in Yerevan, told Al-Monitor, “Air cargo is BS. There is no demand."

An Armenian source with close knowledge of the talks acknowledged, “Rapprochement with Turkey has yielded nothing. Turkey has entrenched itself further in the Caucasus. Through these negotiations, it’s become more of a player.” The source, who sought anonymity in order to speak freely, observed that rather than use its growing influence to de-escalate tensions between the sides, “Turkey is encouraging Azerbaijan in its maximalist demands.”

Gohar Iskandaryan, the head of the Iran studies department at Armenia's National Academy of Sciences, said, “For the last two centuries Russia had the upper hand. Turkey is rising in the Caucasus.”

Yerevan-based analyst Tigran Grigorian concurred, saying, “Russia has become overly dependent on Turkey and Azerbaijan since the start of the war.”

The reality is far murkier. Laurence Broers, an associate fellow at Chatham House, said, “The geopolitics of the Caucasus is still very much in flux. In 2020, it looked as though Russia and Turkey had sealed the region’s fate by ejecting the Western powers and ‘regionalizing’ the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process.” Broers told Al-Monitor, “But Russia’s catastrophic invasion of Ukraine has shattered its standing as the security patron of the South Caucasus and driving a new strategic intimacy between Moscow and Iran.”

In Ukraine, the Kremlin’s discredited war machine increasingly relies on Iranian drones. Turkey’s fabled Bayraktars proved crucial in the defense of Kyiv. In the South Caucasus, much as in Syria, Russia, Iran and Turkey’s goals are both competitive and complementary.

“I think we’ll continue to see a very dynamic situation among these powers, almost a kind of ‘hyper polarity,’ with no single hegemon in control,” Broers said.

With its mountain vistas and ancient churches, Armenia’s Syunik region is a hiker’s paradise. Image taken Jan. 19, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

From Russia with no love

For Armenia’s Pashinyan, Russian peacekeepers’ inability — or Moscow's unwillingness, many say — to fend off the Azerbaijani “protesters” blocking the Lachin corridor appears to have been the last straw. On Jan. 10, Pashinyan said he had informed the CTSO that Armenia would no longer be hosting the bloc’s annual peacekeeping drill. “Their lack of response means that Russia’s military presence in Armenia not only does not guarantee Armenia’s security, but on the contrary, creates threats to Armenia’s security,” Pashinyan groused.

Indeed, there are many, including senior Armenian officials, who believe that Russia favors Aliyev’s Zangezour corridor scheme as this would give Russia direct land access to Turkey and a further means to bust Western sanctions. Russian peacekeepers would control the route and Armenian forces would notionally be deployed with them. But the prevailing consensus is that the Russians can’t be trusted and anti-Russian sentiments among ordinary Armenians are growing by the day. Dozens of protesters were detained in early January during an anti-Moscow rally outside Russia’s 102nd base in the city of Gyumri on the Turkish border. The crowd chanted slogans calling for Armenia to pull out of the CTSO and for Russian forces to leave.

“Moscow has made clear that it does not want to alienate Baku or its ally Ankara. From the high ground that they now control inside Armenia, Azerbaijani forces could sweep down to take more territory, which would cut off southern Armenia from the rest of the country and force Yerevan into more concessions. Some worry that if Baku grows frustrated with the pace of talks, it could well try its luck at exactly this manoeuvre,” the International Crisis Group commented in its new report.

On a recent afternoon in Goris, Russian peacekeepers stood outside their base smoking cigarettes, visibly bored. Others browsed the shelves of a richly stocked local supermarket before plumping for bananas and tangerines.

“When we ask them, ‘Why aren’t you doing anything to help us?’ they just stare blankly or say they were sent here for military service and don’t know what they are actually supposed to do,” said a shopkeeper who makes custom patches and other paraphernalia for the Russians. “Look,” he said, holding up a baseball cap in the colors of the Russian flag and embroidered with a giant “Z,” a symbol of support for the war on Ukraine. He declined to be identified by name.

Gevorg Mirzoyan, a construction worker in Akner who is helping Salbuntz repair his shattered home, agrees that Russia can no longer be counted upon. “I think Iran is a good ally,” he told Al-Monitor. Deepening discord between Iran and Azerbaijan is bolstering such sentiments across Syunik.

Locals in Goris, Armenia, produce custom patches and other paraphernalia for Russian forces stationed there, Jan. 20, 2023. (Amberin Zaman/Al-Monitor)

In a further provocation, Aliyev has begun to play the ethnic card. Iran has a sizable Azeri minority thought to equal 15-20% of its population. In a Nov. 25 address, Aliyev asserted, "We had to conduct military exercises on the Iranian border to show that we are not afraid of them. We will do our best to protect the secular lifestyle of Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis around the world, including Azerbaijanis in Iran. They are part of our people."

Aliyev went on, “There are schools that teach in Armenian in Iran, but there are no schools that teach in the Azerbaijani language. How can this be? If someone says that this is interference in internal affairs, we absolutely reject it. Azerbaijan's foreign policy is as plain as day. We did not and do not interfere in the internal affairs of any state."

The comments mark a big shift. Firdevs Robinson, former Caucasus editor for the BBC who closely monitors the region, told Al-Monitor. “Azerbaijani nationalists’ feelings of solidarity with Iran’s Azerbaijani ethnic minority and their hostility towards Iran for siding with Armenia are nothing new.” She went on, “What has been notable is the growing unfriendly rhetoric coming from Baku in recent months.”

The SWP’s Azizi believes that Azerbaijan’s efforts to sow separatism in Iran won’t have much of an effect. Azizi told Al-Monitor, “The ethnic factor in the recent Iranian protests has been quite marginal. Also, it's highly unlikely that Iranian Azeris would want to leave an authoritarian regime to join another one.”

Interviews with several Iranian-Azeri truck drivers parked along the road between Meghri and Goris suggested that Azizi may be right. Huseyin Ismaili, who has been carrying Iranian oil to Armenia for the past 15 years, told Al-Monitor, “Yes, it’s true that Azerbaijan is telling us to stand up for our culture and rights and all that. We hear this stuff on Azerbaijani and Turkish television channels.” He added, “They tell us we need freedom. We have enough freedom. Iran is good. Iran is beautiful. No thank you, I say.”

Still, Iran’s Azeri population would certainly react to armed confrontation with its ethnic kin across the border. “The only real option Tehran has, and is working on, is to return to its traditional policy of supporting Armenia against Azerbaijan,” Azizi said. “I cannot even rule out the possibility of Iran arming Armenia with drones and the like.”

Back in Yerevan, Iskandaryan, the academic, says she would welcome such a move.

“If we have to choose between annihilation as a nation or sanctions from America, I prefer the latter,” she said.

Editor's note, Feb. 3, 2023: An earlier version of this article stated that Russia reportedly has yet to deliver over a billion dollars' worth of arms paid for by Yerevan. The alleged figure is in the hundreds of millions.