As 2015 came to a close, the Grand Ballroom of the Conrad Hotel in Manhattan presented a diverse tableau: Around the meticulously set tables sat Muslim women wearing colorful headscarves with oriental motifs, African-American clergymen from Queens, Jewish students from a Turkish charter school and veteran New York state politicians.

The lights dimmed. Murat Omur, president of a New York-based nonprofit called Peace Islands Institute, used two giant screens to present an overview of the past year’s highlights, which included setting up hospitals and orphanages in Haiti.

As the guests enjoyed their entrees, the institute silently auctioned a Barack Obama autograph and a pair of boxing gloves. By the end of the night, the Peace Islands Institute had raised half a million dollars, Omur said.

There were brief speeches. “I admire the vision set forth by honorable Fethullah Gulen,” said Leonard Petlakh, vice president of the American Zionist Movement. “Principles and teachings of Fethullah Gulen are the antidote of fundamentalism,” said Victor Hall, pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Queens.

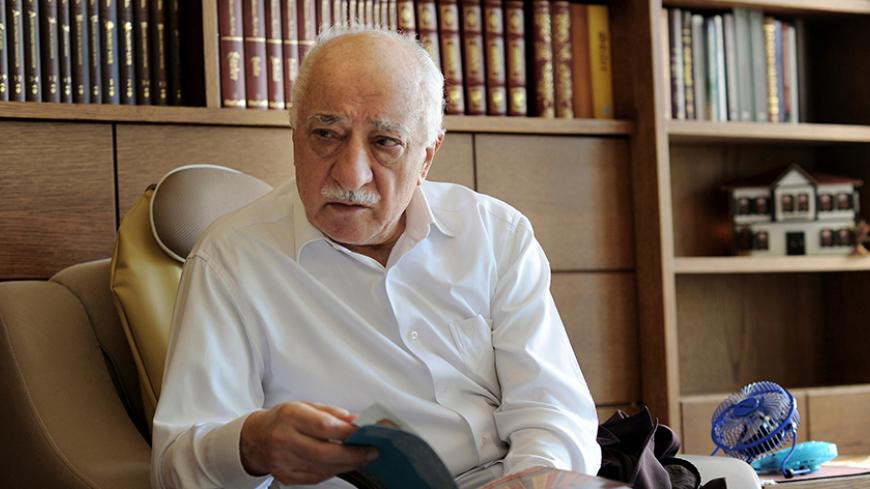

Gulen was nowhere in sight. He was at his Pennsylvania farmhouse, which he has seldom left since settling in the United States in 1999.

The Muslim religious scholar from Turkey preaches a moderate form of Islam — one that regards terrorism as blasphemy and a woman’s headscarf as secondary to education. In the United States, there are a handful of nonprofit organizations that list him as their honorary president.

Gulen is also a wanted man. He is accused in Turkey of leading a terrorist organization that has attempted to topple the government. A Turkish court has issued three arrest warrants for him. He is also being sued in the United States, in a civil case alleging human rights abuses. Gulen and his expansive following face an uncertain future.

Only three years ago, Time magazine included him among the 100 most influential people in the world. Estimates of his congregation’s size range from 3 million to 6 million people worldwide and the worth of affiliated institutions is estimated to be in the billions, according to author and journalist Claire Berlinski. Schools set up in his name have spread across 150 countries.

Today, Gulen risks losing it all in an all-out conflict with Turkey’s most powerful politician, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. They espouse two different schools of Islamic thought, but their conflict involves power more than theology. To understand the story of Gulen’s rise to influence in Turkey and his fall from grace, one must return to 1938.

A timeline of Fethullah Gulen's life. Click here for a full screen

That year, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s secular founder, passed away. Also that year, Gulen’s father, Ramiz Gulen, returned home from a town center in frustration. A civil servant had refused to register the name of Gulen's son because the functionary found “Muhammed Fethullah” to be too Islamic, according to a biography by journalist Faruk Mercan. Ramiz Gulen could only register his son’s name four years later. As the imam of an eastern Turkish village, Ramiz Gulen wanted his son to follow in his footsteps.

Fethullah Gulen’s movement started with a small group of middle-class Turks who followed him as their imam. Later, when he was stationed in metropolitan cities such as Izmir and Istanbul, wealthy Muslims also began to gather around him, writes Dogu Ergil in his book “Fethullah Gulen and the Gulen Movement.” They not only considered Gulen a spiritual leader but also a guiding intellectual, a life coach.

During the 1960s in Turkey, leftist and rightist students constantly clashed in the streets. Universities frequently closed. Gulen believed the new generation had lost its moral compass, and could only regain it through education, Mercan writes.

The followers opened their first dormitory in 1976. Just a few years later, the 200-bed facility in Izmir would become one of the best high schools in the country, according to Ergil’s book. Schools in other major Turkish cities such as Istanbul, Bursa and Ankara followed.

The followers also set up college preparatory courses. According to Helen Rose Ebaugh, a sociologist who has conducted research on the movement, 75% of the students who took the courses would pass the university entrance exam, compared with 25% for those who did not take the courses. College prep quickly became an important venue in which to discover promising recruits.

In 1991, a group of Gulenist businessmen established their first international school in Azerbaijan, according to Mercan's book. Schools in former Soviet republics and even in non-Muslim countries such as Mexico and Japan mushroomed.

The alumni of Gulen-affiliated schools graduate from some of the best universities in the world. They settle in various countries, “establish businesses and support those who would follow after them; they are also encouraged to disseminate the humane Islamic values in the environment in which they live,” writes Ergil.

Some Gulen alumni become successful businesspeople or influential politicians in various countries. According to Ebaugh, the followers give on average 10% of their annual income to the movement.

“Some say, 'This is a big project. It could not have come out of a religious scholar’s head,'” Gulen once told Mercan in an interview. “True; I never claimed that these projects came out of my head. … These are all blessings of Allah.”

The “big project” got even bigger with the expansion of the Gulen movement into the business world. “He [Gulen] has encouraged business activities that would be guided by a set of principles and values,” said Ahmet Kurucan, a follower who has known Gulen for 35 years.

Kaynak Holding, for instance, founded in 1979 by Gulen followers in Turkey, comprises 23 companies in a variety of industries ranging from information technology to retail.

The movement even had its own bank.

After the military coup of 1980, Turkish generals who regarded themselves as the guardians of secularism became highly suspicious of Gulen. Disturbed by his sermons, the soldiers accused him of trying to overturn the government and to establish Islamic rule. "Wanted" posters hung at some of the busiest bus terminals in Turkey, featuring photos of a few dozen leftists and a headshot of Gulen, writes Mercan.

After six years on the run, Gulen was arrested. But Prime Minister Turgut Ozal “became Gulen’s guarantor” and he walked free, said Mehmet Kececiler, a former government minister and founding member of Ozal’s party.

Ozal is widely regarded as the leader who opened Turkey to the rest of the world. He was a great US ally who wanted to see Turkey lead the Turkic republics that had just separated from the Soviet Union in 1991. The schools Gulen’s followers established in those countries fit both Ozal’s and the United States’ visions.

“In order to prevent the resurrection of the Soviet Union, the US encouraged the [international] schools,” said Kececiler.

When Ozal passed away, Gulen walked behind the procession for hours. “Ozal is the only person whose loss made me cry as much as my father’s,” Gulen told Mercan.

Gulen had the support of the political establishment. Some secularist politicians who stood behind him saw his movement as a significant force that would stymie the rise of political Islam.

His health was faltering. He had been diagnosed with diabetes in the early 1980s and now had cardiovascular problems. “He was like a corpse walking,” said Kurucan.

In 1999, Gulen visited the US for a checkup. After several months, a private Turkish TV station aired a leaked video featuring grainy, edited clips from Gulen’s sermons.

“You must move in the arteries of the system without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centers,” he was filmed saying to his followers. “You must wait until such time as you have gotten all the state power, until you have brought to your side all the constitutional institutions in Turkey.”

After the video surfaced, many accused Gulen of infiltrating the Turkish bureaucracy, judiciary and the police.

Hanefi Avci was a police commissioner at the time. “People spoke about the presence of Gulen’s followers inside the police force, but there was no apparent criminal activity,” Avci said. “Only after 2006 did certain police officers start to show deeper allegiances to the movement than to the state.”

In 2000, Gulen was accused of setting up an illegal organization to undermine the secular foundations of the republic. Had Gulen returned to Turkey, he could have been arrested. He chose to stay in the United States. The case lingered for eight years and Gulen applied for permanent residency.

About a decade before the video began circulating, a US-based Turkish association had bought a 150-acre farm in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, for $250,000, Mercan writes. Gulen started living in the farmhouse.

Just before breaking his fast in Ramadan, he would turn on the TV and gaze at people praying inside the mosques of Istanbul. “You could see his watery eyes as he watched those scenes,” said Kurucan, “He is the leader of a movement, but at the end of the day he is a human being.”

Gulen was acquitted in 2008. Although he described his time in the United States as “imprisonment,” he refused to go back to Turkey. “I shall return whenever the conditions are ripe,” he told Mercan.

By 2008, conditions in Turkey had begun to change after Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP), an Islamist party, had come to power.

Gulen never met Erdogan in person after the latter became prime minister in 2003, said Alp Aslandogan, a spokesman for the Gulen movement. Erdogan was a political Islamist from the school of Necmettin Erbakan, a politician Gulen had refused to join in 1969, according to Mercan.

However, the Turkish military’s threat to intervene against the AKP brought Erdogan and Gulen closer. “His [Gulen’s] position and the movement participants’ position has been that the military should not have a direct role in domestic politics,” said Aslandogan, “AKP and the movement participants were in solidarity at the time.”

In 2007, the Turkish police found 27 hand grenades in an Istanbul slum. Investigators believed the weapons were to be used by an ultra-nationalist terrorist organization called Ergenekon, in a coup against the AKP government. Waves of arrests began. An unlikely mix of generals, journalists, academics and underground figures were taken into custody. The number of defendants quickly rose to 275, some of whom spent years in jail without a verdict.

Nedim Sener is a Turkish journalist who was investigating the alleged involvement of Gulen-affiliated policemen in the murder of a Turkish-Armenian colleague. Soon after, he was accused of being a member of the Ergenekon terrorist organization and spent more than a year in jail.

“The [Ergenekon] operation — which had the goal of ending military tutelage — became an attempt at mass destruction targeting all opponents of the government and of Fethullah Gulen’s congregation,” Sener said. “It happened with the cooperation of policemen, prosecutors, judges and journalists who were followers of Fethullah Gulen.”

Ebaugh doubts the allegations that the movement infiltrated the police in large numbers. The percentage of followers in the police would not exceed the percentage of Gulenists in the general public, the US sociologist said.

Hanefi Avci, a former police commissioner who was arrested soon after publishing a book about the movement, disagrees. “They placed their own people at the head of the counterterrorism units in Istanbul and Ankara, and reached the level of power to lead the investigations,” he said. Avci estimates the percentage of Gulen followers in the police force at the time of the Ergenekon arrests at 20%, a proportion far higher than the percentage of Gulen’s followers in Turkey.

Members of the movement deny the allegations that their brethren in the police or the judiciary take direct orders from Gulen.

Gulen and Erdogan were still on good terms, but the tide was about to turn. The tension had already begun to build. “It was learned that profiling [of Gulen’s followers] was going on for years under the AKP administration. This is something AKP leaders had promised to stop,” said Aslandogan.

Ahmet Sik is a Turkish journalist who spent 376 days in jail during the Ergenekon operation. According to Sik, both the AKP and the movement did not trust each other. “A Gulenist police commissioner had been intercepted by the FBI while [he was] transporting the movement’s digital archive to the United States,” Sik said, based on what he learned from a high-level bureaucrat. “[In reaction,] Erdogan ordered Hakan Fidan, head of Turkish intelligence, to prepare a report [about the movement.]”

The rift just kept growing. In 2012, prosecutors who were alleged Gulen followers attempted to subpoena Fidan for a case regarding a Kurdish terrorist organization.

The next year, the infuriated prime minister announced that the college preparatory courses — often operated by Gulenists — would be shut down. In the following months, Erdogan began to pressure heads of state to close the Gulen-affiliated schools in their countries. According to Sabah, a pro-government Turkish daily, some schools in Azerbaijan, Gabon and Senegal shut down.

The movement allegedly responded to Erdogan’s offensive with a high-level corruption probe in which businessmen close to the prime minister, senior bureaucrats and three ministers’ sons were arrested.

Later, a supposed tapped phone conversation surfaced on social media. In the recording, which cannot be independently verified, the prime minister allegedly talks with his son about disposing millions of dollars. Erdogan called the crackdown a “dirty conspiracy” and blamed Gulen.

“Mr. Gulen categorically denied having any influence over the judiciary members or the police force members and he supported the investigations on the principle of accountability,” said Aslandogan.

Since then, it has been all-out war. In November, 122 people — including Gulen himself — were indicted. Gulen is accused of tampering with an investigation and managing an armed terrorist organization, among other allegations. He is facing aggravated life imprisonment without parole, the most severe sentence in Turkey’s penal system.

Although the battle is not yet over, Gulen has lost on many fronts. The Turkish government has tightened its grip on Gulen-affiliated companies. In October, an Ankara court appointed trustees to take control of Koza Ipek Holding, one of the biggest enterprises managed by Gulen followers. The court linked the company to “FETO,” the abbreviation for "Pro-Fethullah Terror Organization."

The Turkish banking watchdog BDDK had already taken control of Bank Asya, a Gulen-affiliated bank, claiming it failed to meet legal criteria.

“The pattern is that Erdogan is trying to end all organizational activity of the movement,” said Aslandogan. He said that if this continues, the movement "is going to be reduced to individuals.”

The Peace Islands Institute fundraiser at the Conrad Hotel took place 10 days after Gulen was indicted in Turkey. It was more important than the previous years’ galas, since the movement was being stripped of its most important financial resources. As the pianist played lobby tunes and the illusionist made the water inside a cup disappear, most of the guests seemed unaware of the immediate threat their movement was facing.

As the friends of Peace Islands Institute took the last selfies of the night, Gulen was at his Saylorsburg home. His health is fragile and the stress caused by Erdogan is not helping.

He does not sleep well anymore, said Aslandogan. The fear of losing him keeps some of his followers awake, too. “Some may be concerned about the [future] management of the movement,” said Kurucan.

Aslandogan has an inkling about what a future without Gulen may look like. “I think his spiritual role as a guide on core issues is going to be assumed by a group of people,” he said. “It is not going to be an individual anymore, because there is no individual who can fill those shoes.”